FRIGHTFUL STORIES

SPOOKY SLIDESHOW

Decomposing face pendant (rosary bead), 1510–1530

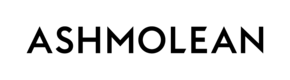

Magical Battle of Frogs by Utagawa Yoshitora, 1864

Grotesque coconut cup & cover, c. 1510–1600

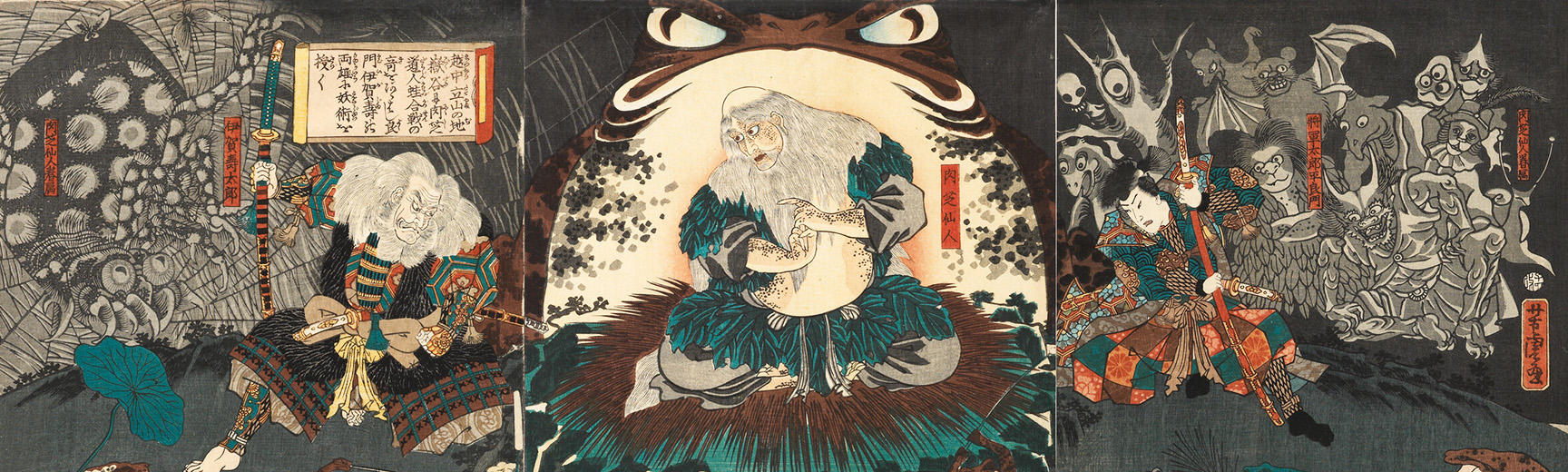

The King of Limbs Radiohead album cover, 2011

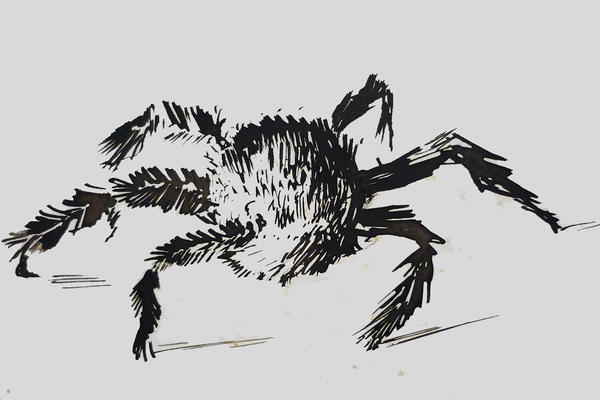

Spider-like creature, by Edward Coley Burne-Jones, 1890s

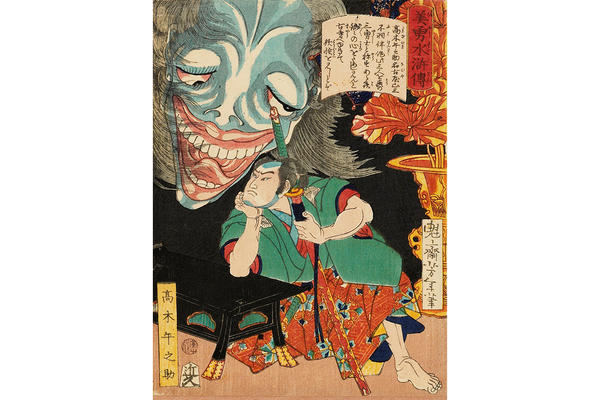

Takagi Umanosuke with ghost by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, 1866

Ojime skeleton and bat, 19th century

Saul and the Witch of Endor by George Jones, 1830–1860

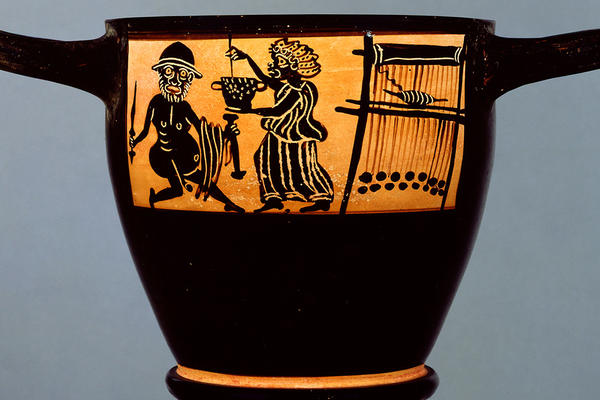

Ancient Greek pottery depicting Odysseus and sorceress Circe, 4th century BCE

Ariel riding on a Bat by Joseph Severn, 1820

Skull watch/timepiece, c.1640

Earth Spider netsuke

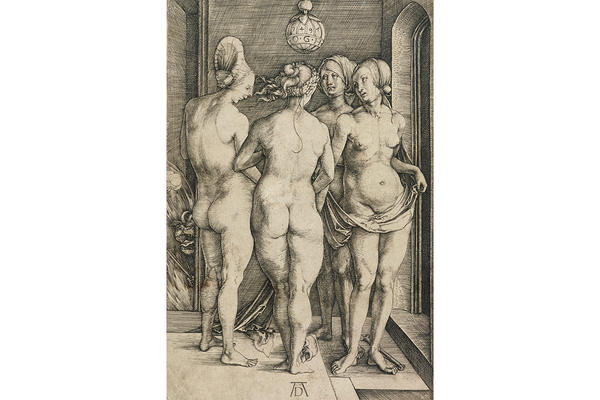

The Four Witches by Albrecht Dürer, 1497

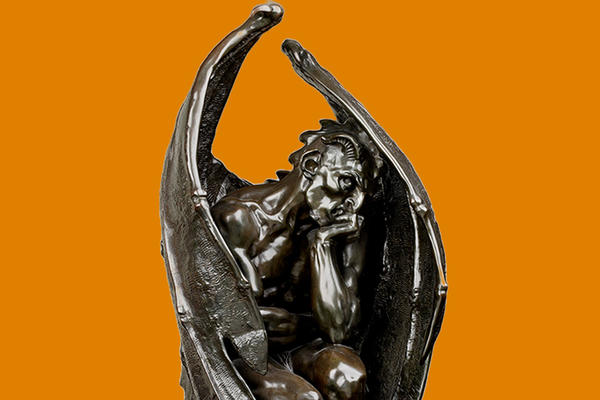

Satan (detail) by Jean-Jacques Feuchère, 1833–1834

The Witches' Dance, 1720

KNIGHT, DEATH AND THE DEVIL

By Albrecht Dürer, 1513

In this large, allegorical engraving by the German printmaker Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), we see a mounted knight in the foreground, while Death rides beside him clutching an hourglass. The Devil is on the right, behind the knight's horse, in the form of a grotesque animal. The knight is accompanied by a dog. A lizard lies beneath the horse's feet, and a skull sits on the tree-stump in the bottom left corner.

It's a finely-executed depiction of calm, steely resistance to evil and mortality. Dürer was probably influenced by the writings of his friend, the humanist philosopher Erasmus of Rotterdam.

Although the anatomical details distinguish the engraving as a masterpiece of naturalistic observation, it's arguably the fantastic elements that give the picture its power. John Ruskin used the engraving to make both moral and practical points in his teachings. It was presented by him to the Ruskin Drawing School and is now in the Ashmolean's print collection.

Not on display

WA.RS.STD.009

View the print in the Western Art Print Room

MEMENTO MORI SKULL RING

Memento mori gold, enamel and diamonds skull ring, Europe, 1600–1700

Death from disease, famine or war was an ever-present reality in the 16th and 17th centuries. Memento mori rings (from the Latin ‘remember that you must die’) reminded the wearer of the brevity of life, and the need to prepare for death and the afterlife. The prospect of death served to emphasise the emptiness and fleetingness of earthly pleasures, luxuries and achievements.

This is the finest memento mori ring in the Ashmolean’s collection. Diamonds are set in the skull’s eye sockets and nose, and in the crossbones. These would have sparkled and flashed in the light, drawing attention to the ring’s macabre message.

The ring was presented to the Museum by C.D.E. Fortnum in honour of Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee in 1897. It's one of the remarkable collection of over 800 rings, also by C.D.E. Fortnum. The collection was given to the Museum with the aim to help us become ‘an institution of the first importance for teaching and illustrating the development of art applied to both small and larger objects’.

Currently not on display (due to the Rings cabinet being renovated in the the Arts of the Renaissance, Rings Gallery, 56)

WA1897.CDEF.F476

COMPOSITION WITH BIRDS AND BATS

Composition with Birds and Two Bats by Jan van Hessel, the Elder

1650–1679

This dramatic composition depicts two flapping bats in the centre of the painting, with one of them fiercely protecting their pups. They are being mobbed by an assortment of diving birds, both domestic and exotic, with some deceased birds lying around.

The painting was made by Jan van Kessel the Elder, one of the finest Flemish still-life painters of the 17th century. He painted mainly small-scale pictures of flowers, fruit, vegetables and insects in oils on copper. This particular work is therefore more unusual in its subject matter. It’s from a set of four similar small paintings by the artist on show in the Museum.

On display in the Daisy Linda Ward Still-Life Paintings Gallery 48 on level 2

WA1940.2.47

SKULL AND CROSSED-BONES FUNERARY MEMENTO MORI

Memento mori chiaroscuro woodblock print, 1720s

This woodblock print was made by a French or Italian artist and dates to the 1720s. It’s a chiaroscuro woodcut printed in black, grey and silver, mounted on a board with a piece of knotted string at the front. It has traces of melted candle wax and shows signs of once having been fixed to a stick or pole, so it was most likely carried during a funeral procession.

Such images were probably once quite common at funerals. The skull and crossed bones - an emblem often found on old tombs and monuments - would have reminded those attending the funeral of their own mortality, acting as a Memento Mori. The flickering candlelight reflecting off the silver and white surfaces of the print would have looked quite ghostly, hinting at the horrors of Hell and decay.

Although several of these prints would have been produced, they were not the sort of object that would have been considered worth preserving, so most would have been discarded. This is the only known surviving example of an ephemeral funerary chiaroscuro print.

Not on display

WA2017.70

View the print in the Western Art Print Room

GHOST OF OIWA (DETAIL)

The ghost of Oiwa emerges from a lantern to frighten Tamiya Iemon, Japanese woodblock print, 1845–1848

By the renowned artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi, this ghoulish woodblock print depicts an episode from a famous Japanese ghost story, the Tale of Oiwa.

Oiwa is a young woman who is poisoned by her husband, Tamiya lemon (a dishonourable samurai). After an agonising death, her spirit returns to haunt him. Here, he recoils in horror as Oiwa’s deformed face emerges from a lantern. Smoke from the fire below turns into strands of Oiwa's hair and ropes and vines come alive as writhing snakes. Even the yellow flowers look like accusing eyes.

View this print and others by appointment

LUCKY BATS TOBACCO CONTAINER

Tonkotsu with lucky bats attached to a netsuke and ojime

18th century – 20th century

An intriguing object, this little 8cm tobacco container (or 'tonkotsu') is made from coconut shell with red lacquer and is carved with bat motifs. The bat is a symbol of good luck in Japan and China.

Attached to the tonkotsu with silk cords are a wooden netsuke in the form of a rocky landscape and an ojime bead of bone and horn.

The tonkotsu would have been worn suspended from a man’s kimono sash. The netsuke would have been tucked behind the sash to act as a toggle and the ojime would have kept the lid tightly closed.

On display in the Japan 1600–1850 Gallery 37, Level 2

EA1978.147

GHOST KIMONO

Silk Jūban Kimono, 1901–1930

This ethereal, silk jūban (non-formal) kimono is dyed with a design of a female ghost who peers through the window of a house, floating above autumn grasses in a long white burial robe.

She is an example of a yūrei, a tormented ghost who remains among the living in order to seek revenge or take care of unfinished business.

Her pale face, wispy hair and dangling, bony hands express her misery. In Japan, ghost stories are associated with the hot and humid summer months, when a scary ghost story sends welcome shivers down the spine.

The kimono was recently acquired by the Museum.

Not on display

EA2023.14

Explore our ghost and demon prints in a previous online exhibition

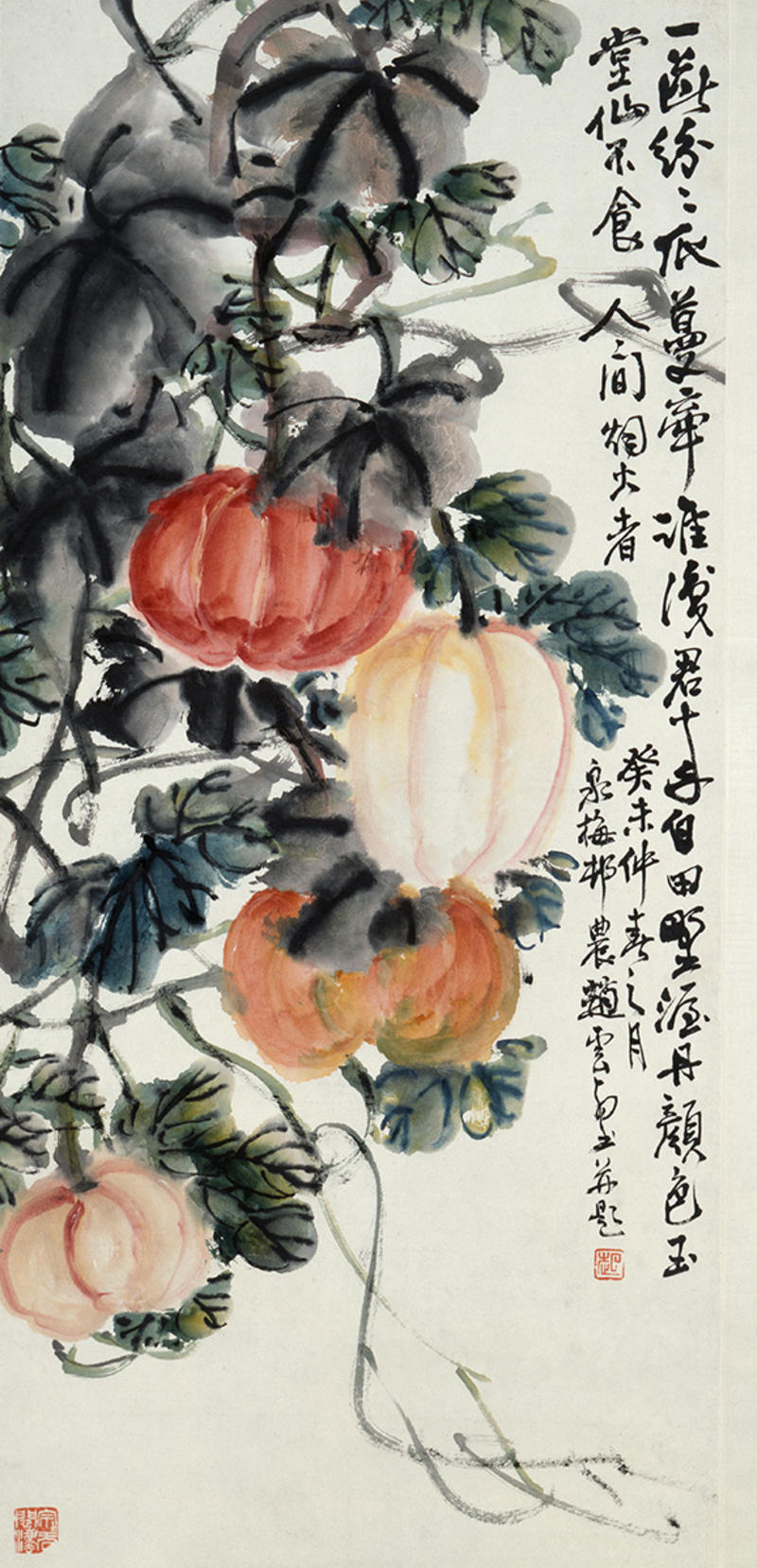

PUMPKIN VINE

Pumpkin vine hanging scroll by Zhao Yunhuo, 1943

This Chinese hanging scroll features a lively brush painting of a pumpkin vine, in ink and colour. It’s by the artist Zhao Yunhuo, who was from Wuxian (present-day Suzhou) in Jiangsu province. Zhao specialised in flower painting and was a very highly regarded pupil of the renowned master of Chinese art, Wu Changshuo.

Pumpkins represent fertility and good fortune, and in parts of southern China it is traditional to give newlyweds a 'stolen’ pumpkin at the Mid-Autumn Festival to encourage the future growth of their family.

Not on display

EA1966.164

View this by appointment

CERAMIC PUMPKIN

Mother Pumpkin II by Kate Malone, 2004

At 20cm high, this impressive sculpture made by ceramic artist Kate Malone was fashioned in stoneware and moulded as a pumpkin with a twisted stem. The underside has two air holes, is fired unglazed in a salt kiln and has caught salt vapours on its surface.

Describing her love of pumpkins, Kate says, 'it has a beautiful shape and it looks corporal like a bosom, a belly or something plump and juicy.' She has made many ceramic pumpkins, large and small, mostly glazed, making this a unique example.

Pumpkins are seen as good omens to ward off the evil spirits of Halloween, because they symbolise abundance at harvest time. The history of pumpkin carving, associated with a ghoulish figure called 'Jack O'Lantern' - although popularised in America - goes back to the Celtic tradition. People used to place root vegetables, decorated with scary faces, on their doorsteps to frighten the devilish Jack away.

On display in the Sickert and his Contemporaries Gallery 63, level 3

WA2005.103

WATCH OUR 'SCARY OBJECTS IN THE MUSEUM' VIDEO

https://www.youtube.com/embed/EgDk8ilDwHM?rel=0&cc_load_policy=1