REBUILDING THE PALACE OF MINOS AT KNOSSOS

5-minute read

By Andrew Shapland

Sir Arthur Evans Curator of Bronze Age and Classical Greece

And thanks to John Pouncett, Oxford University School of Archaeology

From the restoration and visions of the renowned archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans to the digital 3D model constructed for our current Labyrinth exhibition, follow the story of rebuilding the famous palace at Knossos with exhibition curator Andrew Shapland. (The above header image shows the dramatic entrance to the Labyrinth exhibition, photo courtesy Wolf Media UK.)

A CONTROVERSIAL CONCEPT

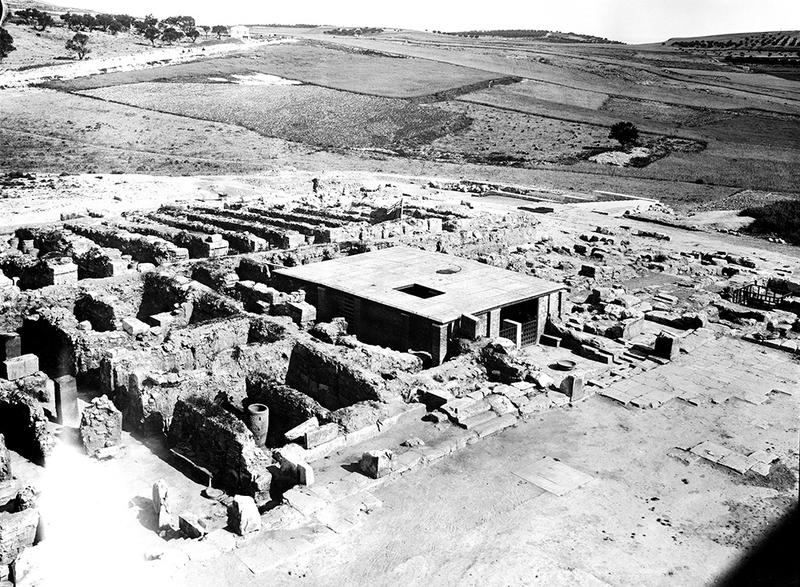

Sir Arthur Evans began excavating the building he called ‘the Palace of Minos’ at Knossos in 1900 and continued working there until 1931.

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of his work was his decision to restore the Bronze Age palace, in use from around 1900 to 1350 BCE, using modern building materials.

Nevertheless, the Palace of Minos is now the second most popular archaeological site in Greece, attracting almost a million visitors a year.

In this article, we examine Evans’s reconstructions and show how digital technology enables us to strip away some of these later additions. Many of the photographs and illustrations below feature in the exhibition.

COVERING THE THRONE ROOM

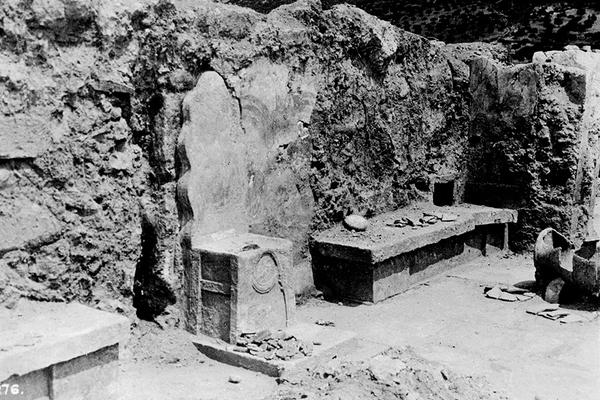

In April 1900, after only a few weeks of excavation, Sir Arthur Evans’s workers started to uncover a room with a throne against the wall.

Photograph of the Throne Room of the Palace of Minos at Knossos, 1900, GB 1648 AJE/3/1/12/26/1 © Ashmolean Museum

As a contemporary photo shows (above), the remains of a fresco showing a palm tree were still in place.

Photograph of the roofed Throne Room at Knossos, c. 1901. GB 1648 AJE/3/1/3/27/1 © Ashmolean Museum

Once that first season of excavation had finished, with all the excitement of discovery, it became apparent that some of these rooms needed protecting.

An architect, Theodore Fyfe, had been employed to record the building and finds, but now he was asked to come up with a way to conserve the palace.

The next year he put up a simple stone and timber shelter. This kept the rain out but soon had to be replaced once the timber started to rot.

REBUILDING THE GRAND STAIRCASE

The next architect to work at Knossos, between 1904 and 1905 was Christian Doll. He had a more complicated problem to solve since he was responsible for restoring the Grand Staircase opposite the Throne Room.

Photograph of the Grand Staircase of the Palace of Minos at Knossos during restoration. Arthur Evans is at the back dressed in white. On his left is his assistant Duncan Mackenzie, and the architect Christian Doll. GB 1648 AJE/3/1/8/20 © Ashmolean Museum

The staircase descended over seven metres below the Central Court, over several storeys. Following winter rains, it had partially collapsed. The Cretan workers on the excavation, who came from the surrounding area, were enlisted to help rebuild it.

Doll’s solution, here and elsewhere in the palace, was to use steel joists and vaulted brick ceilings to reinforce the ancient architecture.

The imprints of wooden columns had been found in the excavation so these were replaced in concrete. The aim was to restore the original appearance of the building using modern materials.

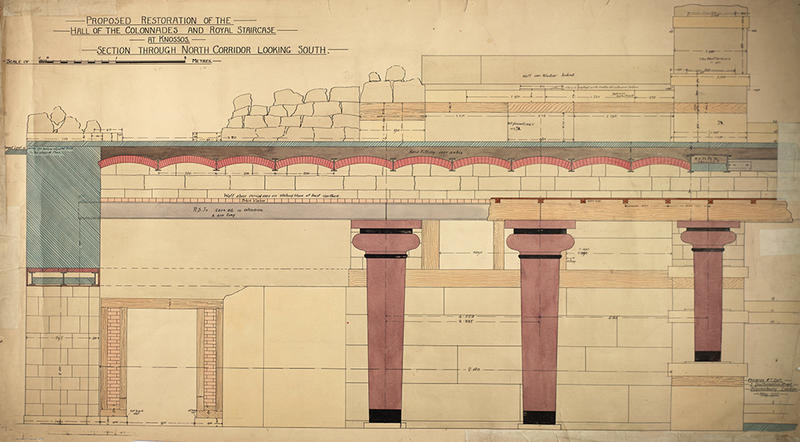

Proposed Restoration of the Hall of the Colonnades and Royal Staircase at Knossos: Section Through North Corridor Looking South (Evans Architectural Plans GS/HC/2b) 1905, Christian C. T. Doll (1880–1955), ink & watercolour, 63x116cm, GB 1648 AJE/4/2/3/3.

REIMAGINING THE PALACE

The last architect to work at Knossos, from the 1920s, was Piet de Jong. He had a new material at his disposal, reinforced concrete.

He worked with Evans to reimagine how the palace might have been, a process Evans termed ‘reconstitution’. Inevitably the clean straight lines of concrete gave the building a modernist air.

This has always divided opinion.

One visitor, R.G. Collingwood suggested in the 1930s that ‘the first impression on the mind of a visitor is that Knossian architecture consists of garages and public lavatories’.

Central Court from south-east with restored Stepped Portico, Throne Room and North Entrance, c.1930. GB 1648 AJE/3/1/12/45/1 © Ashmolean Museum

Colourful frescoes were also restored on the walls. These were based on the fragmentary remains of frescoes found in particular places, but had been completed by artists working for Evans. Often the reconstruction on paper provided the inspiration for the physical reconstruction, adding a layer of interpretation along the way.

Reconstruction drawing of the Throne Room. Published 1935 in 'Palace of Minos' after the original watercolour by Edwin J. Lambert (1881–1928), 1917

In some places Evans had de Jong restore the palace as an ancient ruin, as it might have looked in the later Classical period. For Evans this showed how the ruins of the palace might have inspired the myth of the Labyrinth.

This work has been criticised by later archaeologists because there is little evidence to support reconstructions such as the north entrance bastion with its fresco of a charging bull.

For some visitors, however, this helps bring the palace to life. There is evidence for frescoes of life-size bulls on the walls of the palace here, so the overall effect evokes the Bronze Age even if the details are problematic.

The north entrance bastion in 2019. Courtesy of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Heraklion

RESTORING THE RESTORATIONS

The Palace is now owned and run by the Greek State. The Heraklion Ephorate of Antiquities is responsible for the management of the site and over the last few decades has been undertaking a comprehensive programme of repairs.

The Evans reconstitutions are over a century old in some cases and themselves need restoration.

The Ephorate has also installed wooden walkways to limit the damage of visitors to the Bronze Age building as they walk through 3,500 year-old stone doorways. It is a mammoth task but the aim is to secure this popular tourist site for future generations.

DIGITAL RESTORATIONS

There is no suggestion that the Evans restorations should be removed, but it can be difficult for archaeologists and visitors alike to disentangle the 20th-century reconstitutions from the 2nd millennium BCE building. One way to do this is using digital technology.

For our Labyrinth exhibition, the Oxford School of Archaeology created a 3D model of the Palace of Minos. This was created using a computer program called ArcGIS Pro.

Knossos palace 3D model in the Labyrinth exhibition. Photo by Wolf Media UK

It's based on the most recent plan of the palace produced by the Ephorate of Antiquities of Heraklion. Present wall heights were compared with the Ashmolean’s excavation archive in order to try to restore the palace to its pre-reconstruction state.

This process is ongoing and the 3D model will continue to be refined using drawings, photographs and notebooks from the Sir Arthur Evans Archive. The 3D model is a representation of the palace as excavated by Evans.

It isn't a reconstruction of the palace as it would have looked in use at any moment in time, because the building was itself remodelled several times over the course of its 600-year lifespan.

https://www.youtube.com/embed/OTIJPPf2wuE?rel=0

Above: Digitised version of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Heraklion’s plan of the palace created by the Oxford University School of Archaeology (courtesy of Heraklion Ephorate of Antiquities and John Pouncett)

The 3D model was printed for display in the exhibition to show visitors the excavated remains. The process of creating and printing the model in itself highlighted the close links between the excavation and restoration of the palace and the difficulties of documenting Evans’s exploration of the site.

The next phase of the project, which will continue after the exhibition, is to integrate the Sir Arthur Evans Archive into the model. Our hope is that visitors will be able to explore Evans’s discoveries in each room with the click of a mouse.

The Ephorate too has recently released two apps for visitors to explore the Palace.

One provides a tour of the palace.

The other allows visitors to experience the palace in Augmented Reality as it might have looked in the Bronze Age using AR (Augmented Reality). These initiatives show the opportunities that digitisation provides for exploring and reimagining the Palace of Minos.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the Heraklion Ephorate of Antiquities for their collaboration on the 3D model of the palace of Minos.

The 3D model was created by John Pouncett and Karl Smith with the aid of a grant from the Al Thani Collection Foundation. The print was funded by the Patrons of the Ashmolean Museum.