KRASIS BLOG

ABOUT KRASIS (2017-2023)

Krasis is a unique, museum-based, interdisciplinary teaching and learning programme, which began life at the Ashmolean in 2017, devised by classicist (and historian of ancient Boeotia) Dr Sam Gartland and Teaching Curator Dr Jim Harris. In 2018, the programme won a University of Oxford Humanities Division Teaching Excellence Award. Michaelmas term 2022 was its 15th iteration.

Each term Krasis gathers eight early career researchers from the University of Oxford (the Ashmolean Junior Teaching Fellows or AJTFs) and 16 current Oxford undergraduates and taught-postgraduates (the Krasis Scholars) for a series of object-centred symposia, devised and delivered by the teaching fellows, who each address a shared theme from the standpoint of their own discipline and their own research.

For the Krasis Scholars, the programme offers first-hand insight into what an academic pathway might look like and provides a rare opportunity to learn directly from researchers outside their own subject, whilst contributing from within their degree specialism. For the AJTFs, it offers a forum for interdisciplinary dialogue and a ready, able team of students and colleagues to explore creative, imaginative approaches to collaborative, collections-based teaching.

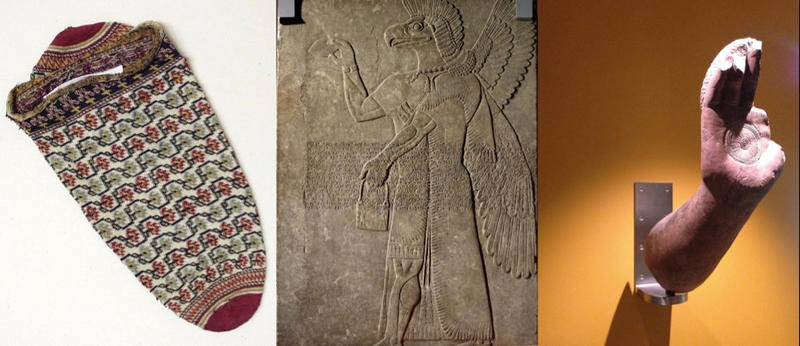

Over the past five years, Krasis has seen series on Power, the Body, Absence, Presence, Performance, Devotion, Imitation, Voices in Conflict, Movement/Transition, Play, Danger, Identity, Constraint, Opening, Becoming, Belonging, Re-Use and Container. We have used objects ranging from kimonos, musical scores and Tibetan musical instruments to Renaissance bronzes, newspaper advertisements, palaeolithic handaxes. and ancient Egyptian magic wands.

Our Teaching Fellows and Scholars have come from Classics, English, History, Economics, Fine Art, Chemistry, Archaeology, Anthropology, Egyptology, Assyriology, Russian, Japanese Studies, German, Earth Sciences, Engineering, Politics, French, Portuguese, History of Art, Arabic, Physics, Statistics, Islamic Studies, Development Studies, Geography, Music, South Asian Studies, Philosophy, Linguistics, Theology, Women’s Studies, Experimental Psychology and Law, and from almost every college of the University.

Competition to join Krasis is fierce, and the growing number of former Scholars returning as Teaching Fellows testifies to its impact on participants. But the question of what actually happens each week has remained mysterious outside the walls of the Museum.

This blog, written by programme participants, aims to shed some overdue light on the enigma.

Welcome to Krasis.

KRASIS 15

During Michaelmas term 2022 we explored the theme of Believing, from the perspectives of AJTFs working in English, French, Theology, Late-Antique and Central Asian History, Linguistics and Anthropology.

KRASIS 14

During Trinity term 2022 we explored the theme of Container, from the perspectives of AJTFs working in English, Central Asian History, History of Science, Medieval German, Linguistics, History of Art and Engineering.

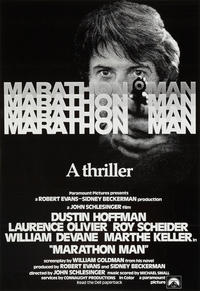

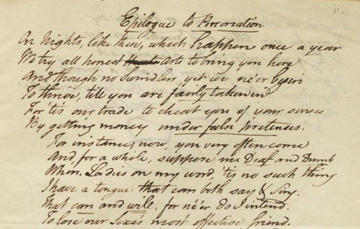

Week 1 was devised and led by AJTF Madeleine Saidenberg, whose doctoral research examines Shakespeare, adaptation, and national identity in 18th-century Ireland. She also co-convenes the TORCH network Queer Intersections Oxford (QIO) and hosts the forthcoming ‘Practice Makes’ podcast for the Re-Imagining Performance Network. Before starting the DPhil, Madeleine worked in theatre and television in New York, Dublin, and Morocco, and as an assistant director and dramaturg in the West End and off-Broadway.

This blogpost was written by Krasis Scholar Caitlin Kelly, a second-year undergraduate reading English at Somerville College.

Theatre

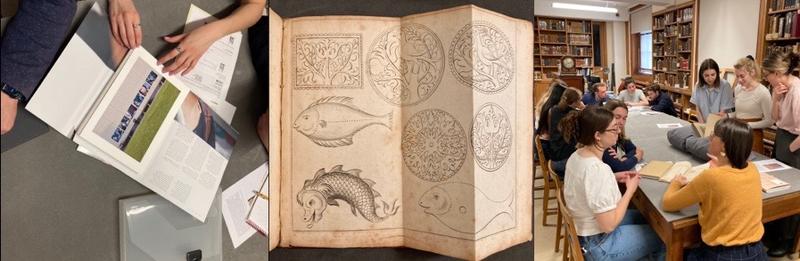

Krasis 14 began, as Krasis does, at the harpsichord – our physical anchor during eight disorienting weeks of intellectual unravelling. After a journey through labyrinthine corridors to the Eastern Art study room [it’s not that far! Ed.], AJTF and 18th-century Irish theatre historian Madeleine Saidenberg began her symposium by prompting us to describe the scene directly facing us as we sat at the table.

For me, this meant an array of delicate pottery stored behind glass. For the scholars on the opposite side of the room, a series of obstinately opaque metal cupboards, like filing cabinets. Even unlocked, behind each door were just reams of black boxes and envelopes: a seemingly infinite regress of archival Matryoshkas.

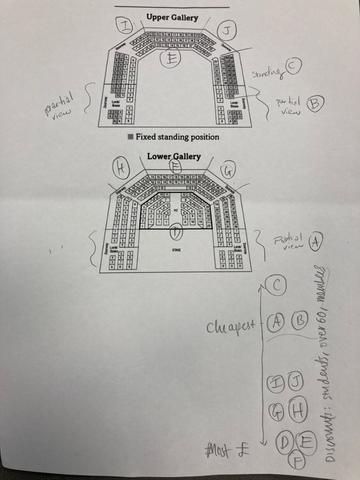

Assessing these juxtaposing perspectives, I was struck by how the contrast between the filing cabinet and its glass counterpart mirrored that of backstage and frontstage. How behind the illusion of effortless, contained performance is an intricately organised network of artifice.Madeleine split us into groups, giving each an architectural plan of a theatre, tasking us with fixing the price of each seating area.

Armed with the staging for the Playhouse Theatre’s recent production of Cabaret, my colleague Bethan Downs and I deliberated before deciding that the seats directly on and above the stage should be the most expensive: the production seemed to deliberately play with the boundary between audience and performance, therefore placing a premium on those most immersive seats where theatregoers could become a part of the Kit Kat club themselves.

Sharing our findings amongst the rest of the scholars we heard about a range of spaces from the Almeida theatre to the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, each with their own idiosyncrasies available for productions to harness.

As we each explained our pricing strategies, we considered how theatre as an art form often occupies an exclusive container unattainable to those who cannot afford either to participate in or watch it and how this is in some degrees a modern phenomenon.

Placed in the role of theatre designers, set designers, and directors, the exercise highlighted the malleability of the stage as well as how ‘immersive’ theatre, which appears to break the container of the fourth wall is nonetheless carefully micro-managed.

So, what happens when the audience refuses to be contained?

We were each assigned an account of a theatrical riot ranging from the Abbey Theatre riots during the first performances of The Playboy of the Western World in 1907 to the Astor Place Shakespeare riots of 1849 in which at least 25 people were killed. Behind each were latent tensions around class, race, and gender, whose containers somehow failed, ruptured by the performances staged. It struck us how, as a meeting point for a host of clashing and intersecting identities, the theatre can be a volatile space in which the boundaries of social containment are disputed or reinforced.

Theatre can simultaneously be a locus of conservatism and radicalism. Hearing about W.B. Yeats’s introduction of lights-down performances and the austere rules of behaviour he enforced on the Abbey Theatre’s audiences highlighted how theatrical mores have evolved over time; the unruly chatter of 17th-century Restoration audiences seems alien to a 21st-century audience for whom Yeatsian silence is the standard.

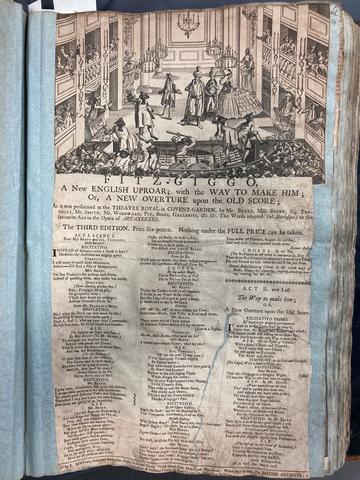

Moving on, we examined the 18th-century broadside print, Fitz-Giggo, a new English uproar, a satire on a riot which occurred during a performance of Thomas Arne’s Artaxerxes at Covent Garden in February 1763.

As we read how the actors feared that the audience would ‘throw the Seats about our Ears/And tear the Boxes down,’ we discussed the decline in theatrical audience invasions and the way popular sport seems to have replaced theatre as a mass cathartic space. Most of us had heard of or witnessed pitch invasions but never come across one on stage.

After all this talk of rioting, we made our way to the cafe in a nice orderly fashion to take tea.

Resuming fully caffeinated, we were met by a curious, gold-framed pendant featuring a portrait of a man. Each of us was encouraged to share one thing we observed about the object as we passed it around the room; the only rule being we had to state only what we saw, not what we could interpret. From this, we gradually pieced together a picture of the object: that it had a hook and could be worn; that the man depicted was in the latter stages of his life and dressed formally; that hair which matched the colour of the man’s own was carefully plaited and incorporated into the back of the pendant.

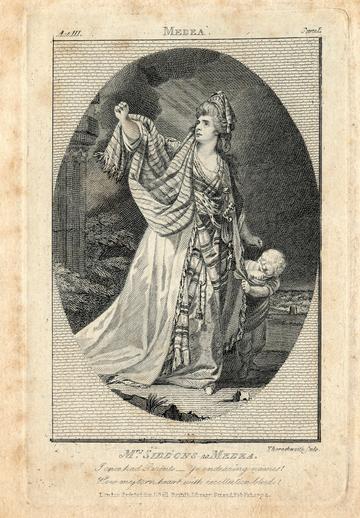

Eventually, it was revealed that the object allegedly depicted the Georgian Irish actor Charles Macklin, famous for playing Shylock in The Merchant of Venice and for breaking with the established declamatory style to introduce a more naturalistic mode of acting. Perhaps a souvenir, family memento, or piece of mourning jewellery, the pendant seemed to question whether human essence can be contained.

Springboarding from this, we moved to a collection of portrait prints of Macklin both on and off stage, alongside a broadside advertisement for Macklin’s own play Love à la Mode, a comedy in which four suitors, English, Irish, Scottish, and Jewish, compete for the hand of the heroine Charlotte. As we surveyed these images, Madeleine provided an overview of Macklin’s life and career, tracing his childhood in County Donegal through to the heights of his fame on the stages of the West End. Learning about Macklin’s chameleonic ability to portray and write characters of different classes and cultural backgrounds prompted a rich discussion around whether the actor is a neutral, universal container.

In hindsight, this discussion was underpinned by two assumptions. Firstly, that the boundary between actor and role, container and contained, should be fully blurred, that the two should become one and the same. Secondly, that audiences may interpret theatrical representations as microcosms for entire communities with this having the dangerous potential to underplay the heterogeneity, even the humanity, of marginalised groups. These unsaid principles seemed to reflect 21st-century tastes for naturalistic acting and non-allegorical characterisation.

Our conversation centred on whether the identity of an actor should align with that of the role they mean to inhabit, a pertinent question in light of growing calls for representative casting.

In this vein, we discussed the appropriateness of straight, cisgendered actors playing queer characters, of able-bodied actors playing disabled characters, and wondered if non-representative casting constrained performances and hampered authenticity.

Ultimately, a consensus emerged stressing the importance of representative casting as a form of reclamation for marginalised communities. Turning back to Macklin we debated whether his portrayal of Shylock humanised the Jewish community by individualising Shylock as three-dimensional and fallible, or if he crystallised negative stereotypes by playing into antisemitic tropes.

The discussion then moved on to accents; we dissected the way in which RP (Received Pronunciation) has been taken as a neutral form of English and how this has resulted in an erosion of regional accents within the acting community.

Born and raised in Norfolk, I reflected on how as a child I’d been taught to iron out any semblance of an East Anglian twang, how I had never seen how my family talked properly represented on stage or screen until very recently with Sean Harris’s performance in The Goob (2014) and that of Ralph Fiennes in The Dig (2021).

We equally considered instances where the presence of a certain actor interrupts the melding of container and contained, preventing the audience from fully immersing themselves in performance.

Bethan raised how she found the casting of Elizabeth Moss as Offred in The Handmaid’s Tale jarring, given her membership of the Church of Scientology. Afterwards, we debated Tom Cruise’s acting ability (Jim firmly on the side of Cruise as great actor).

Reflecting on this conversation after the session called to mind productions which have taken a more iconoclastic approach to the idea of containment.

John Barton’s 1973 production of Richard II saw the roles of the titular king and the usurper Henry Bolingbroke alternated between performances. The audience was unaware of who would be playing who until the performance started - each night opened with an actor playing Shakespeare who crowned a masked Richard Pasco or Ian Richardson as that night’s King Richard II.

Danny Boyle’s 2011 production of Frankenstein at the National Theatre employed a similar strategy. Jonny Lee Miller and Benedict Cumberbatch would take turns playing Victor Frankenstein.

Barton and Boyle’s self-reflexive productions highlight how breaking the container between actor and role can foreground the fragility of human power structures, as well as the commonalities we often desperately try to deny between ourselves and those we deem different.

The final third of the symposium concentrated on the Museum as a performative space, inviting us to consider whether we can transcend the containers of viewer and viewed.

Leaving the Eastern Art study room, Madeleine led us to the Weldon Gallery of Baroque art.

The first painting we encountered was Truth Presenting a Mirror to the Vanities of the World, an anonymous work from the early 1600s.

The piece shows an allegory of Truth who looks upon the viewer. She holds a set of scales in her left hand and an outward facing mirror in her right, adjacent to the mirror is a skull resting on top of a manuscript. Truth invited us to meet her gaze yet the inability of the mirror to reflect us was disorienting, it decidedly prevented our assimilation with the artwork. Read alongside the presence of the skull, perhaps the mirror’s refusal to reflect reveals the insignificance of our mortal containers relative to a grand cosmological scheme, a protest against material concerns. Alternatively, does the mirror relegate art to a contained realm of artifice unable to truly reflect or interact with the real world?

The anonymity of the artist equally seemed to question whether visual and literary artworks require a single identifiable creator to contain them, whether we can reconcile ourselves to unknown or collaborative genesis.

Madeleine then guided us to Blowing Hot, Blowing Cold, an oil painting by Matthias Stom, depicting a feast scene from Aesop’s Fable ‘The Satyr and The Traveller’ in the style of Caravaggio.

Madeleine encouraged us to stand directly before the painting, to try to immerse ourselves in the banquet before us. Though an empty space at the table occupying the foreground seems to invite the onlooker to take a seat, the painting’s grand scale and dramatic chiaroscuro seemed to reinforce the border between art and reality.

After the session, I learnt that the painting depicts a satyr’s amazement at how a peasant man can warm his hands with his breath yet with the same air cool a spoonful of soup. The subject seemed particularly relevant to the session’s refrain on contradictions held within a single container.

The session drew to a close at the Treby toilet service, an opulent silver dressing table set gifted by George Treby to his wife Charity on the occasion of their marriage in 1725. I couldn’t help but wonder what the display did not show; whether immense suffering had been required to produce the toilet service and to sustain the luxurious lifestyle of the Trebys.

The extensive array of brushes, cosmetic compacts, and jewellery boxes in the toilet service prompted us to discuss the exertion behind calm, collected facades. The effort required to produce the containers we present to the world and whether such endeavours are in vain. As we debated this, our gaze was met in the mirror before us, yet the morphed reflections in the silver trinkets below underscored the impossibility of true containment.

To return to the image of the infinite filing cabinet confronting us at the start of the symposium, my first Krasis has taught me never to rest on my laurels. The container of knowledge can never be fully unpacked, or filled, its contents and contours are constantly evolving.

I eagerly await the next existential crisis Krasis has in store.

Week 2 was devised and led by AJTF Dr Linus Ubl, who is Departmental Lecturer in German at Somerville College. His research draws together linguistic and historical approaches to medieval German literature, as well as reception studies and the question of how history is told in the present, i.e. books, movies and popular culture.

This post was written by Krasis Scholars James Titterington and Renée Trepagnier, both Masters students. James is reading English at Regent's Park College; Renée is reading Classical Archaeology at Hertford College.

Museum

James: Inevitably, Krasis 14 began for us all at the harpsichord. Rather than being whisked away to the New Douce Room, the session started with a walk around the museum. Each group was assigned a floor and tasked with wandering around for ten minutes, all the while thinking about the kinds of containers that might be found within the Ashmolean.

Dr Linus Ubl was in charge this week and we walked the third floor with him, watching out for containers. As it turns out, this museum (like every other) is full of them. Most obviously there are the glass cases. But then in certain cases, there are cases within cases. In other cases, there are no cases at all. Linus encouraged us to think about why this might be.

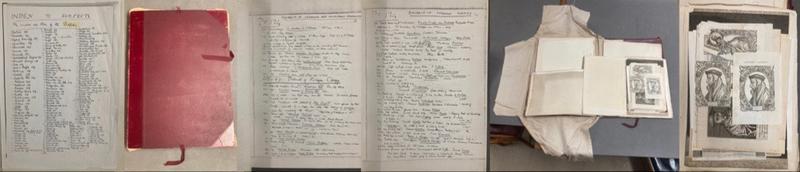

When we got back to the New Douce Room, each group presented their findings on containers: the gift shop as container; language and labels as containers; the museum itself as a meta-container. Then things got properly underway, and Linus brought out one of Douce’s creations, an album which contained a puzzling collection of prints. We were encouraged to think about reading practices and how a book might facilitate these. Francis Douce was famous for cutting up incunabula and printed books, and rearranging them in new, often inscrutable, compilations of his own design. Linus dissuaded us from condemning this as a purely destructive act, and suggested we focus on the “new” objects as containers.

[Biographical note: Douce resigned from the British Museum in 1811. His reasons for doing so have since become infamous. Reason number thirteen is a highlight. He bemoans the “fiddle faddle requisition of incessant reports, the greatest part of which can inform them of nothing, or, when they do, of what they are generally incapable of understanding or fairly judging of.”]

However, Douce’s album was just one of four books that was examined. In addition to Douce 367 there was a cookbook focussed on making pie cases; some French poetry printed on Korean paper and stored in a bespoke box. Renée, Linus and I were presented with an entire folder, containing photobooks, exhibition records and receipts from the artist Sigune Hamann. One of the books was in fact a poster which functioned as a folder for photographs, which were records of a previous exhibition. For a group on the lookout for containers it was very pleasing indeed.

So far, the session had been stimulating, fascinating and (happily, in the New Douce Room) completely free from fiddle-faddle of any kind.

Renée: So, having examined books as containers, Linus now turned the investigation to the function, history, and properties of empty boxes. James, Linus, and I were given a very large, wooden box with an old label reading “Douce Prints N: 7”. Another label comprised a note: “Empty - moved to solanders”, which clued James and I into the idea that this box was itself an important artifact; the preservation of the empty container indicated its significance beyond its function as an object for holding other artifacts.

The box belonged to Douce’s personal print collection which he catalogued with reference to the compass points denoting the walls of his own print room. Therefore, the box we examined was “North: 7”. Douce’s prints were bequeathed to the University in 1834 in his own containers: not just boxes but also folios and wrappers. which both held his prints and also recorded the organization of his collection. Even empty, Douce’s boxes offer insight into the innovative ways in which he structured, conceptualized and contained his collection. The original intentions and functions of containers, though, are subject to change and objects that act as containers can in themselves become valuable reminders worth preserving - in their own containers. In this case, the Douce box held historical significance and was preserved in the ‘container’ of the Western Art Print Collection in the larger ‘container’ of the Ashmolean.

This thought exercise led smoothly into the final activity in which Linus asked us to re-explore the museum and find an object with multiple layers of containment. James and I selected a brilliantly carved Italian Renaissance chess-set that doubled as a backgammon board on the reverse side. We first identified the set as a container, a box, because of a small, hidden drawer to hold the game pieces. Each carved side-panel of the box acted to contain the two game-boards, while the squares of the chess board contained the game pieces. In a more abstract reflection, James observed that the game pieces were also contained by the rules of the game. Nice. Further levels of containment could be seen in the display case and the Fox-Strangways Gallery itself. In total, we pinpointed approximately 15 layers of containment around this one object.

Other groups tracked down other 'containers'. One examined a US fifty dollar bill, counterstamped ‘lesbian money’, used for political activism. Just as James and I had pondered how the rules of chess limited and contained the movements of the chess pieces, our colleagues questioned how this bill contained notions of economy, activism, identity, and ideology. I believe the discussion concerning layers of containment prompted us all to consider how both materiality and the meanings with we imbue containers - symbolic, political, social, historical, cultural, economic - impact the function, significance, and value of the objects. Containment can happen on a variety of levels and each layer of containment comes with a specific purpose and meaning. Contemplating how objects contain (and are contained by) abstract ideas like game rules or value provides a fresh new perspective for evaluating how we interact with them.

As 5:00pm loomed nearer, Jim rushed us out of the museum before closing. As an archaeologist, I was left considering my own possessions, home, research, and even life in terms of containers. I will doubtless continue these reflections as Krasis continues to introduce new ideas into my consciousness.

Week 3 was devised and led by AJTF Songjun He, who is a DPhil researcher focusing on both synchronic and diachronic Manchu phonology. Manchu is a critically endangered language, once the official language of the Qing dynasty, closely connected to folk music, religion, history. Both the language and the dynasty have left abundant traces in the Ashmolean Museum, from royal certificates of appointment to daily necessities.

This post was written by Krasis Scholars Aspen Warren, who is reading for a degree in the History of Art at Christ Church; and Anna Henderson, who is taking an MSt in Archaeology at St Hugh's.

Language

This week, AJTF and researcher in Manchu phonology, Songjun He sought to further extend our understanding of ‘container’: how can an object store and transfer information, without any direct interaction between maker or ‘storer’, and recipient or ‘user’.

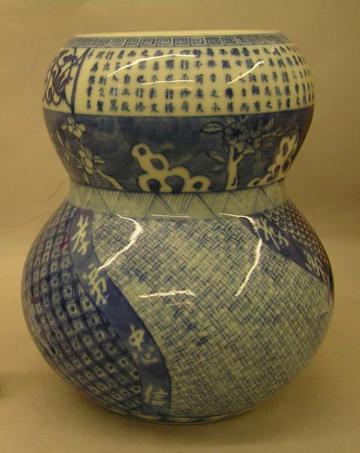

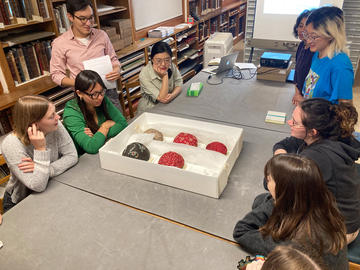

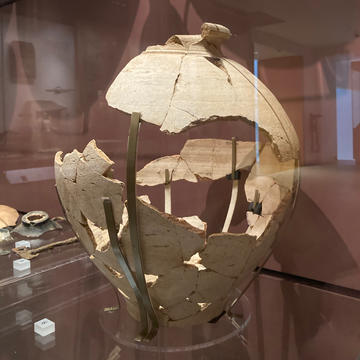

Based, as usual, in the New Douce Room, we were greeted on arrival by a trolley full of material ranging from seals to vases and other, more unknowable objects. Assembling in groups of three, two scholars to each Teaching Fellow, we each chose a treasure and donned our blue gloves…

We selected a blue and white ‘container’, a vase decorated with text, flowers and different patterns and textures. The vase had a sculptural form, with the floral decoration suggesting it might function to hold flowers. Through further observation we noticed how the ornamentation was hand-painted, made obvious through the visible brushstrokes and delicacy of line, with text appearing to be the dominant motif, and we began to ask whether an understanding of what was written was important in trying to assess the purpose of the object.

After speaking with Songjun we learnt the text was derived from Confucian teaching and ‘contained’ a message of loyalty to parents, siblings and the Emperor. Our understanding shifted again after discussion with other groups. We discovered that the jar was, in fact, a ‘mizusashi’, designed to hold water for the tea ceremony, for filling the kettle and rinsing the whisk. The container was thus a practical object which simultaneously served to remind users, when preparing and sharing tea, of the values of family and nation.

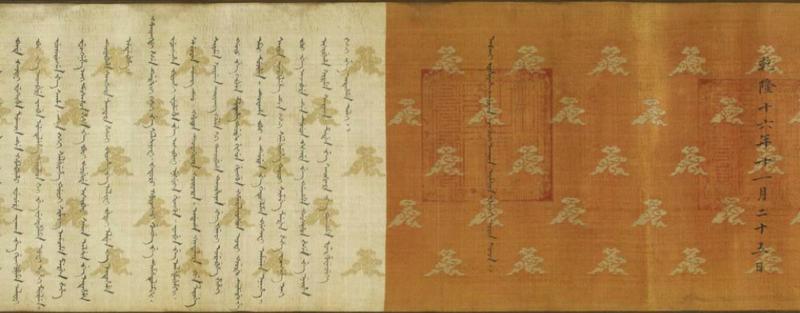

After the break, Songjun took us to the Textile gallery, where, after wandering past the array of beautifully decorated textiles lining the walls, we came to a stop in front of a relatively innocuous glass case. Inside was a partly-unrolled silk scroll. The text on the scroll was an edict written in Manchu script, the now-endangered language that was the official language of the Chinese Qing dynasty.

The scroll records a decree by the Chinese emperor appointing a new governor for the city of Chengdu, capital of the province of Sichuan, and bears his official imperial signature, the body of the text in Manchu script painted onto the silk with ink. We began to consider the scroll as a container; not only did it contain the official edict, but also the imperial seal. Yet the symbols on the scroll were not the only method of containing and transferring information: the weave of the silk itself, with repeated patterns in the background, communicated importance, wealth and authority.

When we returned to the New Douce Room, Songjun gave each group a book from the Hope collection in a language with which we were unfamiliar - Latin, German, French or Italian - asking us to extract what information we could despite our lack.

Many of us resorted to studying the pictures or pointed to odd words we either recognised or were similar to English. We used the publishing information on the front pages to give the books a location and a date and were able to sound out words whose meaning was still unknown. Despite the fact, then, that most of the contents were inaccessible to us, we still managed to understand something.

Songjun then guided us through writing the apparently impenetrable Manchu script. We learned how to connect the various symbols to form the flowing lines that are read vertically top-to-bottom.

We considered what letters and symbols can contain - a shape, a sound - and how, combined in different ways they can then construct new sounds and new meanings, forming more complex containers and communicators of meaning and idea.

Whether or not we can read a script, as in the scroll and the books, the letters still contain this information, waiting to offer it to the next person with the tools to understand.

Week 4 was devised and led by AJTF Mathilde Daussy-Renaudin, who took us for the first time in Krasis history to the University's History of Science Museum. Mathilde is a collaborative doctoral award holder working between the HoSM and University College London. Her work investigates the relationship between science and religion embodied in astrolabes, and considers the categorisation and display of these objects in a museum environment concerned with questions of decoloisation.

This post was written by Emily Rosindell, who is a second-year historian at Exeter College, and Alexandra Egland, who is studying for an MSt in History of Art and Visual Culture at St Benet's Hall.

Astrolabe

Krasis met this week at the intersection of astronomy and astrology, as we investigated the history and technology of astrolabes in the History of Science Museum, under the direction of AJTF Mathilde Daussy-Renaudin. At this crossroads, we were asked to consider how science, religion, and magic might interact within an object: how it might contain all these, and more.

Once gloved, we were able to hold and take apart astrolabes of various sizes and ages and from various places, in an attempt to understand their inscriptions as well as their intricate mechanics. Astrolabes possess multiple moving parts: the rete, or map of the stars, and sometimes several ‘plates’, in addition to rulers and various units of measurement. The plates - metal discs that we discovered were templates for use in different merchant cities - are replaceable and changeable based on the user’s location.

Astrolabes were used by merchants and travellers in the ancient and medieval world and were developed to a high degree by Islamic astronomers and craftsmen. They proved a useful intersection of navigational science and astrology in a manner that revolutionised how an individual could calculate sun and star positions and thus situate themself in space.

Leaning into the Krasis 14 theme of ‘containers’ we thought about what an astrolabe could ‘contain’ – and how we make that clear in a museum. As astrolabes are often double-faced and include several parts, they are difficult objects to comprehensively display to museum audiences. There are intricate and useful details all over the astrolabes’ surfaces that require some contextualisation in order to fully understand the object. These small details acted as containers of the various knowledge bases that determined each astrolabe’s function. They were symbols of education, due to the knowledge required to read them and the economic power required to obtain them, implying that class and pedagogical accessibility are important social containers to consider when analysing these objects.

Astrological and planetary symbols, with inscriptions in Latin and Arabic, all encapsulated elements of the precise function of a particular astrolabe. Some things to consider when looking at individual astrolabes concern their categorisation. Are they Islamic objects or European? Given the geographical and religious contexts of these objects, the information contained was tailored for specific belief systems, points of view, and functions, such as pointing the user in the direction of Mecca in the case of many Islamic astrolabes. Different geographical points of origin would largely correlate to the type of information contained within a single astrolabe.

These handheld objects were containers that possessed all the tools and information for reading the universe and making sense of the world–both physical and metaphysical, as instruments to navigate the geographic and religious pathways of the world. They prompt us to ask: what meanings are stripped from an object when it is displayed in a museum setting and what must be externally learned in order to understand it? Contrarily, what has been foregrounded or distorted now that they are not in use? For objects that are valued for both their utility and beauty, which should we privilege as observers?

The astrolabes, and their relatives such as armillary spheres, compelled us to consider practices such as astrology, now often considered a pseudoscience, but nonetheless founded in scientific observation – of the influence of the moon on the tides, for example. How do we analyse such a pseudo-science as a container of information against what one may consider ‘real’ science, and how can objects like this help us to untangle the relationship between science and magic?

Astrolabes exist within a truly interdisciplinary sphere, useful to different people for different reasons: doctors for tracking illness, explorers for mapping, merchants for travel. They compel us to consider why we so often seek to contain, categorise and label historical learning. The object is multifaceted; it should be displayed as such.

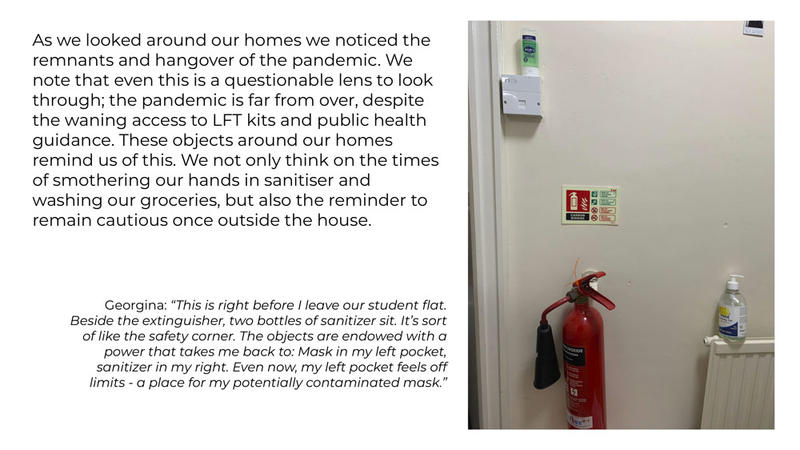

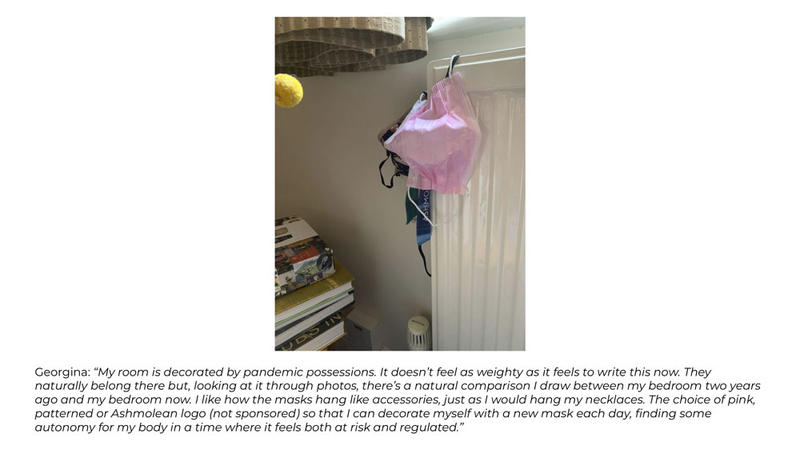

Week 5 was devised and led by AJTF Jiaqi Kang, who is writing a DPhil in the History of Art. Their research examines the relationship between hygiene politics (discourses of health, contagion, and pollution) and art in the postsocialist period in China. As an undergraduate, Jiaqi was a Krasis Scholar in Krasis 05.

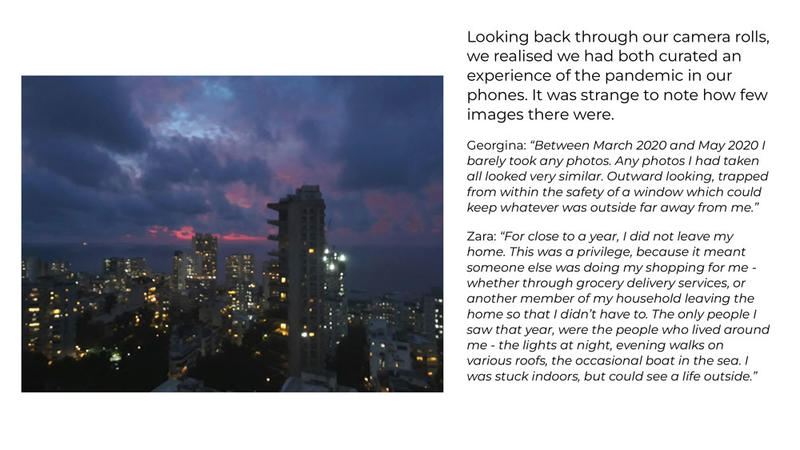

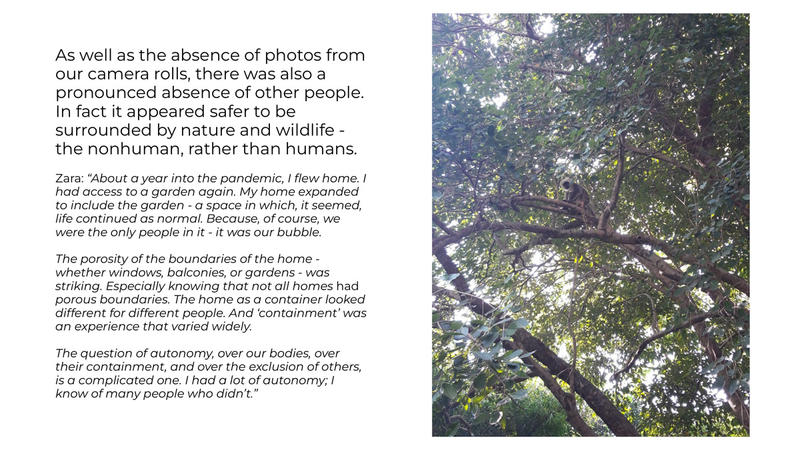

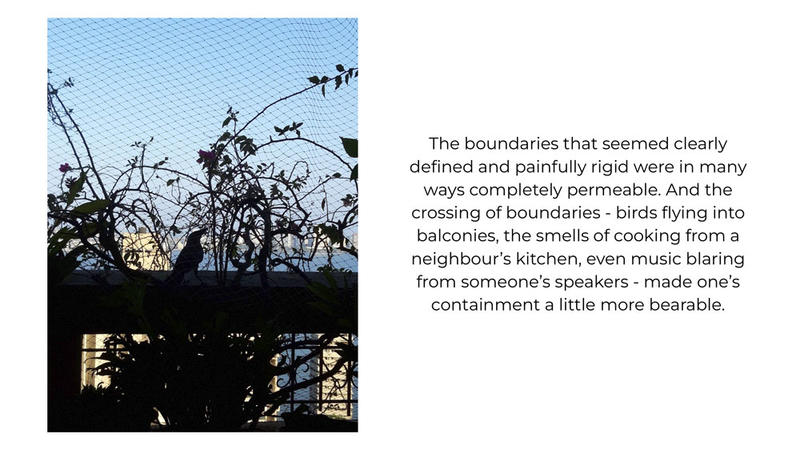

This post was devised and, unusually for the Krasis Blog, formatted as a virtual exhibition by Krasis Scholars Zara Ismail and Georgina Dettmer. Zara is a postgraduate at Wolfson College, writing an MPhil in Modern South Asian Studies; Georgina has just completed a BA in English at Trinity College.

Body

Week 6 was devised and led by AJTF Rachel O'Nunain, a DPhil researcher in English whose work focuses on the pseudonymous, Anglo-Irish writer Michael Field.

This post was written by Lara Garrett, who is reading for an MSt in Women's, Gender and Sexuality Studies at Worcester College.

Discipline

In this week's session, AJTF Rachel O’Nunain encouraged us to consider how containers - categories or areas of study - can be constrictive. While Krasis seeks to break down disciplinary boundaries, we start the programme by introducing ourselves in terms of our subject. Are we, then, being contained? Are we preventing ourselves from seeing how our work connects to other subjects? And what possibilities open up when we reconceive our research through different disciplinary lenses?

With these questions in mind, we moved onto the first exercise. Rachel passed round a cup, which contained everybody’s subject written on a piece of paper. Taking it in turns, we each picked out a slip and considered how to reframe our work in terms of that discipline.

My research looks at late-20th and early-21st century feminism, and, having picked out Classical Archaeology, it took some time to work out how to link the two. I soon realised, however, that Greek and Roman texts have played a crucial role in shaping feminist writing. Homer’s Odyssey, reinterpreted by Margaret Atwood in The Penelopiad, for example, and Ovid’s Metamorphoses, reinterpreted by Ali Smith in Girl Meets Boy.

Reframing our studies in this way, thinking across disciplines, invariably opens up new opportunities. Indeed, making connections between subjects that are often separated out forms the basis of Rachel’s own DPhil research on 19th-century theatre, which looks at connections between naturalistic ‘sexual problem’ plays and the verse-dramas of Michael Field.

Scholars have generally treated naturalistic plays distinctly from verse-dramas. Thinking beyond these categories, however, points to commonalities between the two theatrical forms. Field, for instance, engaged with contemporary dramatic networks, including the plays of their older contemporary, Henrik Ibsen. Field’s work should perhaps, therefore, be reframed in dialogue with – not distinct from - naturalistic theatre.

Katherine Bradley and Edith Cooper, together known as Michael Field

Rachel then revealed to us that 'Michael Field', whom we had all assumed to be male, was in fact the pseudonymous creation of Katherine Bradley and Edith Cooper, who were aunt and niece. Interestingly, their incestuous relationship has often been left out of the literature, scholars not wanting to acknowledge this ‘uncomfortable’ history. Again we see containment at work: scholars attempting to fit Bradley and Cooper into an ‘acceptable’ narrative rather than acknowledging their lives in full.

Week 7 was devised and led by AJTF Roman Osharov of New College, who is a DPhil researcher in History and who wrote this blog post. His doctoral research explores the history of the Russian Empire and Central Asia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries with a focus on the role of knowledge production about Central Asia.

Where is Central Asia (in the Ashmolean)?

The Asian Crossroads gallery in the Ashmolean Museum introduces visitors to the history of Asia in a nutshell. In it, visitors are greeted with objects from Asia ranging from stunning models of camels from China in the period of the Tang dynasty to unique surviving fragments of textiles from Old Cairo. In Week 7, Junior Teaching Fellows and Scholars on the Krasis programme gathered in the Asian Crossroads gallery on the quest to find Central Asia in the Ashmolean Museum and in the contemporary historiography more broadly. What did they discover?

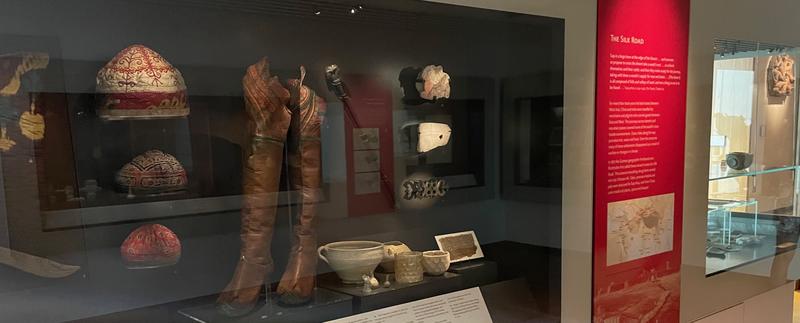

The symposium was dedicated to Central Asian history. The key question was simple, ‘What is Central Asia, and where is it?’ historically and more specifically in the Ashmolean Museum. A quick survey of the galleries and spaces by the participants of the Krasis programme showed that it’s hard to pinpoint Central Asia to a specific location in the Museum. Instead, Central Asian objects, albeit not many of them, are scattered throughout the Museum. They are to be found, for example 'on The Silk Road', in a display housing ceramics, documents and garments; ‘near Iran’, like a ceramic vase in the Islamic Middle East gallery; or ‘between India and Japan’, as seen in the Textiles gallery, where a stunning Central Asian ikat robe from the Robert Shaw collection is displayed between objects from India and Japan.

Elsewhere, another ikat robe brought by Robert Shaw is presented in a display dedicated to the conservation department at the Ashmolean Museum. It illustrates how much behind-the-scenes work goes to preserve textiles so that it could be studied and displayed. Other objects from the Robert Shaw collection – Central Asian textile hats and leather riding boots – are displayed in the Asian Crossroads gallery in a case titled 'The Silk Road'. This shows that at least in the Ashmolean Museum the bulk of objects on display pertaining to the history of Central Asia came from a single collection. This shows the difficulty of studying and teaching Central Asia at Oxford and elsewhere in the UK.

Hence, the main objects that the Krasis Scholars had a chance to examine were Central Asian textile hats from the Robert Shaw collection. Not all Central Asian hats and robes from the collection are on display – many of them are kept in the Museum’s storage rooms in large containers (incidentally, the theme of this iteration of Krasis).

Robert Shaw (1839-1879) was an English explorer and writer who brought the objects displayed in the Museum today from his journeys in Central Asia, which he recorded in his travelogue published in 1871, Visits to High Tartary, Yarkand, and Kashghar. Thus, Shaw was single-handedly responsible for much of our public understanding of the nineteenth-century material history of Central Asia, certainly in the Anglophone world. The garments, like hats and robes, that Shaw brought to London are from Yarkand and Kashgar, but they are almost identical to those worn, for example, in Tashkent or Samarqand in the same period and therefore culturally representative of the entire Central Asian region.

The Robert Shaw collection came to the Ashmolean Museum in the 1960s after the closure of the University of Oxford’s Indian Institute, where it had been kept since at least the 1930s. But the collection was forgotten and for almost 60 years were contained in a storage room. The Shaw collection was rediscovered only in the early 1990s during a routine inspection carried out by Dr Ruth Barnes, a former textile curator in the Museum’s Department of Eastern Art. The garments – which were found in a very good condition -- were exhibited for the first time in 1995 and since then became permanent fixtures in several of the Museum’s galleries.

Elsewhere in the Ashmolean Museum, Central Asian objects were found in the Money gallery. Among the many coins on display, only one or two potentially represent Central Asia, although they are from present-day Southern Anatolia and Northern Pakistan. Finally, a contemporary Central Asian object was found in the Museum shop – a dress advertised as a ‘classic ikat jacket’ and made in a Central Asian country was on sale for £300 (pricey!).

The search for Central Asia showed that there is no dedicated space to Central Asia, at least in the Ashmolean Museum. Instead, Central Asian objects, such as those from the Robert Shaw collection, are scattered throughout the Museum’s many sections. This is especially noticeable when compared to other regions and cultures of the world represented in the Ashmolean Museum, like Indian and Chinese art. ‘Why there is so little interest in Central Asia?’, -- was one of the questions that followed.

For many in our Krasis 14 cohort of Trinity 2022, which includes doctoral students and early career researchers in disciplines ranging from Classical Archaeology to Engineering, Central Asia remains a mystery, both in terms of its history and today. Some said that everyone understands immediately where South Asia, Southeast Asia, and East Asia are, not to mention Russia, China and Iran, that surround the Central Asian states. As one Krasis teaching fellow put it, ‘Central Asia is not on our mental map because it’s not out there’, for example, in museums or (most importantly) in courses that teach history.

But Central Asia, its culture and history have gradually become more visible to the rest of the world, especially since the early 1990s, when the five Central Asian countries became independent in the aftermath of the break-up of the Soviet Union. A recent example is the Gold of the Great Steppe exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum at Cambridge. The exhibition showcased recently excavated treasures of the Iron Age Saka people, like spectacular pieces of gold jewellery and bronze arrows, in the East of modern-day Kazakhstan. The most interesting objects in the exhibition were excavated as recently as a couple of years ago. And in 2022, two of the world's leading museums - the Louvre in Paris and the James Simon Gallery in Berlin - plan to hold exhibitions devoted solely to Central Asia.

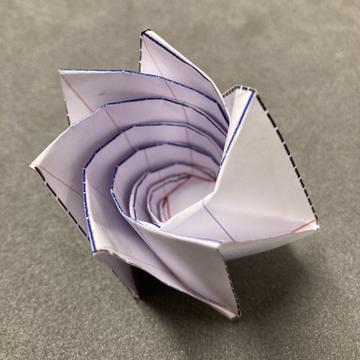

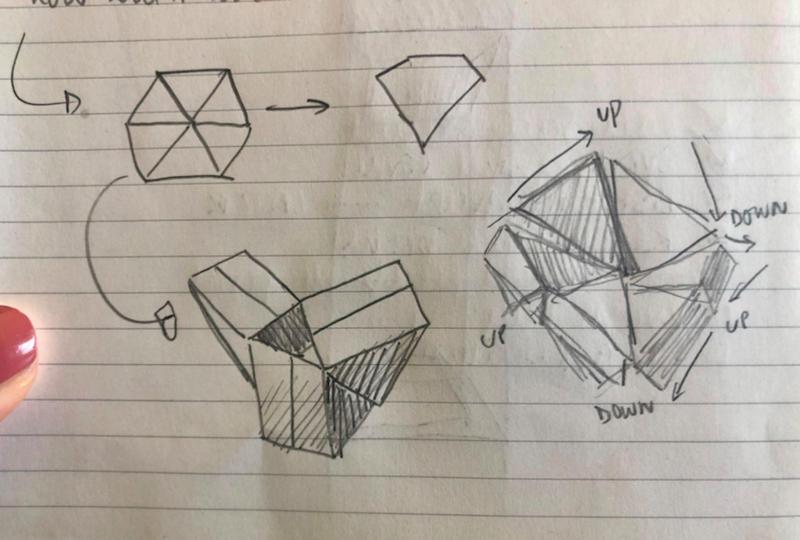

Week 8 was devised by AJTF Chenying Liu, who is is in the 3rd-year of a DPhil in Engineering Science at Wolfson and St Hugh's. Her research spans origami and soft robots. Whilst looking into origami, the Japanese art of paper folding, Chenying goes beyond paper: her work mainly investigates how rigid materials like wood or metal can be folded and what robotic applications they can lead to.

Chenying fell ill at the end of term and was unable to lead the last Krasis of the year. Nonetheless, she gave us tasks that embodied both the simplicity and the extraordinary complexity of the folding technology she has introduced us to.

We folded for all we were worth.

To see and hear Chenying speak about her research (and origami), take a look at this video.

These two reflections on the experience of Krasis were written by Krasis Scholars Stephanie Armbruster and Isabelle Johnsen. Stephanie is an MSc student in Statistics at Somerville College; Isabelle is reading for an MSt in Archaeology at Hertford College.

Krasis

Stephanie: As the first statistics student to ever participate in Krasis, I was definitely an absolute outlier. I would be lying if I did not admit to having felt a little bit out of place and worried about my lack of knowledge about almost everything Krasis touched upon at the beginning. This turned out to be an unfounded and restrictive ‘container’ I put myself into, as Krasis taught me.

As a collective of humans, of students, of statisticians (in my case) we neglect too often that while we have agreed to consider objects and objectivity a common baseline in our objective world definition - a book is a vessel for a certain type of knowledge, an astrolabe is an astronomical instrument explaining the night sky - we all inherently think in different containers, shaped by the experiences, history and skills which underlie every supposedly objective item with subjective meaning. Consequently, my ‘natural science’ perspective was just one additional ‘container’ into which objects could be laid. By discussing with fellow Krasis members, I could distance myself from my own ‘container’ thinking, exploring the perspectives of others.

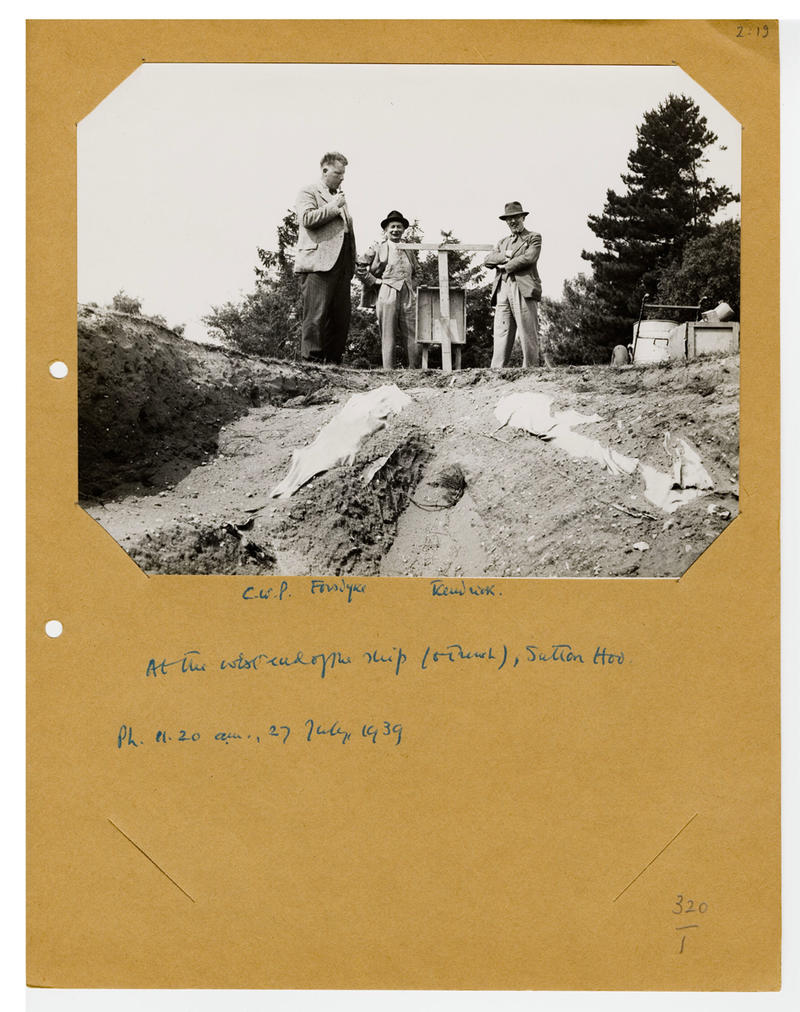

Isabelle: Attending Krasis this semester helped me to rethink how people from other subject backgrounds approach museums and their exhibits. As an archaeologist, you learn that context is everything. However, in Krasis, we learned about how containers can be changed, manipulated, and expanded or contrasted. This made me begin to think about how each profession, and each individual as well, highlights different parts of the context as the “most important”, and how these highlights might greatly differ from one another.

This demonstrated how important interdisciplinary work will be to me in the future. Just as objects have their own histories and are used differently throughout their lifetimes, methods don’t just undergo a linear progression from worse to better; rather, they adapt to fit their own context.

The field of archaeology today focuses on objectivity and scientific approaches during excavation. However, Krasis reminded me that the ‘containers’ into which we put objects during excavation may be changed throughout the objects' lifetime on display. In my experience, archaeologists rarely focus on how these objects that we find in the ground will find a completely new context and take on new meanings based on which ‘container’ a museum puts them in.

In order to understand objects better, perhaps we need to turn outward to alternative interpretations and weave them into our own understandings of the objects and become more interdisciplinary, rather than just becoming more and more specialized and putting that ‘container’ on ourselves and studies.

KRASIS 13

During Hilary term 2022, we explored the theme of Re-use from the perspectives of AJTFs working in English Literature, History, History of Science, Medieval German, Engineering, Musicology and Art History.

Week 1 was devised and led by AJTF Felicity Brown, whose doctoral research examines the relationship between myth and history, performance and politics, and the construction of the 'medieval' in early modern and Enlightenment thought, using social and ceremonial modes of performance to establish how King Arthur was deployed as a symbol of instability and innovation in early modern England.

This blogpost was written by Krasis Scholars Eliza Browning, a visiting student from the US, reading English at Lady Margaret Hall, and Risa Cooper a second-year undergraduate in English at Exeter College.

Re-using Things

The first session of Krasis 13 began at the harpsichord, the weekly meeting point for Krasis Scholars and Junior Teaching Fellows. But the work started when AJTF Felicity Brown led us to the Still-Life Painting Gallery, containing more than 90 outstanding 17th-century paintings by Dutch and Flemish artists.

After an introduction to the still life genre, we split into groups to count occurrences of popular objects in each painting - lemons, tulips, oysters. Whilst our colleagues counted 27 lemons and 42 tulips, we discovered 28 depictions of oysters, often arranged in groups, which raised questions surrounding their symbolism, glistening objects that reflected their surroundings. We also discussed the association of oysters with sexuality, a theme that recurred throughout the wider group conversation.

One of my groupmates noted that the juxtaposition of a closed and open oyster shell may have represented the seen and unseen world, as in the reflection of the painter in a nearby glass. The shape of the open oyster shell also mirrored a nearby timepiece, reminding the viewer of the temporality of this perishable object.

The precarity of the objects at the edge of the table emphasized their fragility, drawing the viewer into the frame. The inclusion of household objects in still life hearkened back to our collective focus on re-use, reminding us that common items often doubled as objects of great value and beauty within works of art.

Asked then to identify unusual objects in other paintings, we discovered a number of strange items including beetles and coins, and an imported Chinese vase that would raise questions about globalisation that we would later explore hands-on with objects from the Ashmolean's collection.

At tea in the Ashmolean Café, we were able to have a longer chat and start to get to know the other members of Krasis. As expected, whilst we ranged in our subject areas, our shared interest in material culture and everyone's friendly and open attitude made it very easy to feel comfortable in the space straight away.

After a short break, we headed to the New Douce Room, a stately yet inviting place full of old leather books and the occasional chime of an antique clock. Dividing into two groups we were lucky enough to handle a cornucopia of beautiful artefacts from around the globe. It was uncanny to see the objects we had studied so closely in brushwork actually before our eyes, and the experience added new depth to the paintings seen prior. My group handled a beautiful pocket watch, a repeated motif in still lives, which was wrapped in a leather case. Our AJTF, Mathilde Daussy-Renaudin, who works at Oxford’s History of Science Museum, commented that the intricate goldwork reminded her of Arabic astrolabes, which in turn prompted Jim to show us a Persian carpet, in which the pattern of the threads resembled the metalwork of the clock.

Alongside these, we looked at a wide range of banqueting objects similar to those depicted in the paintings: glassware, a silver bowl with floral embellishment, a stoneware pot, also mounted with silversmith’s work and a dish decorated with people dancing and playing music around its interior.

We also examined a large, porcelain dish with a floral decoration and gold embellishment, inscribed with the name of Wanli, 14th Ming Emperor of China, but of later date and made for export by the Dutch East India Company. We compared it with a porcelain tankard, created in China during Wanli’s reign but exported and then mounted with silver-gilt fittings by a European goldsmith.

Finally, we were given frames, fabric, shells and silk flowers to create and photograph our own still lives. This practical experience was very thought-provoking as we thought about form, texture, tone and colour - but also the symbolic meaning of certain objects: a watch amongst flowers, for example, perhaps highlighted the moralising message that all beautiful things must fade. Setting up our own compositions highlighted that whilst on one level naturalistic, still lives were essentially artifice: as Mathilde pointed out, many paintings incorporated fruits and flowers not in season at the same time.

Still Life created during Krasis 13 Week 1; photograph enhanced by Laurel Rand-Lewis

Whilst chatting with Felicity, I mentioned that I always used to skip straight past still lives because I found them to be boring and found little difference between the individual paintings. The session completely overturned past prejudices: still lives are actually dynamic, incorporating flora and objects of global trade, and showing implicitly the continual cycles of time: flowers in bud, fruit starting to rot, other objects deployed symbolically to create meaning. Mostly, I am grateful to Krasis for starting to teach me the art of close observation: a little more discipline in looking at things heralded great discoveries.

Week 2 was devised and led by AJTF and historian Elena Porter, whose DPhil research focuses on postwar British cultural policy as it related to the preservation of country houses and their contents.

This blogpost was written by Krasis Scholars Holly Anderson, a third year undergraduate in History at Lady Margaret Hall, and James Green, a second year undergraduate in English and Classics at Exeter College.

Re-using Images

Jane Austen famously begins Pride and Prejudice with a ‘truth universally acknowledged’, so it was fitting that when asked initially in Week 2 of Krasis 13 to sketch (badly) our image of a traditional English country house, we turned almost universally to something vaguely resembling Chatsworth, which stood in for Pemberley in the 2005 film adaptation of the novel. We found common ground on that estate, in its neoclassical columns, bucolic vistas, balconies and terraces and much else besides. But whence came these connotations?

Confronted by a group of objects in the New Douce Room – a small silver container, architectural drawings, and watercolours of country houses – we began to unpack the network of association which supported our shared imagination, seeing ‘exotic’ designs through the lens of architecture and buildings through the lens of cultural appropriation.

This reciprocal framework proved deeply productive, steering us towards two central figures whose architectural voices still echo around many great British buildings of the 17th and 18th centuries: Vitruvius (c. 1st century BCE) and Palladio (16th century CE). In discussing their influence, we were performing something of a nested exorcism: reviving English builders' revival of Palladio’s revival of Vitruvian ideals.

The Palladian aesthetic – of harmony, proportion and symmetry – was one developed (in part) from the (unillustrated) writings of his Roman predecessor. Thus, the buildings we find preserved across the English countryside are themselves preservations of a 16th-century idea of an antique architectural ethos: the cosmopolitan was concomitantly the archaic, true to the spirit of the European Renaissance. Paradoxically then, these magnificent structures, conserved for re-use in the interests of the heritage industry, have long been performing a re-use of sorts.

At this point, we were ready to depart from the English country house and embark on a journey through cultural iconography more broadly defined, including its manifestations in and around the Ashmolean itself.

Examining what the Ashmolean had to reveal about the iconography and changing function of the English country house pushed us to consider the words of historian Robert Hewison in his seminal work, The Heritage Industry:

‘In the twentieth century museums have taken over the function once exercised by church and ruler, they provide the symbols through which a nation and a culture understands itself.’

Like the country house itself – somehow emblematic of English culture, despite its many borrowings - the museum, according to Hewison, possesses a similar function. It has the power to shape our image of different cultures, displaying artefacts selectively, seen through the eyes of a curator to appeal to (educate?) a broad public audience. For many, it is their only contact with other cultures and helps form a worldview, perhaps defined by golden trinkets, dramatically woven garments and ostentatious portraits.

It is interesting to consider how the country house and the enduring role it plays in popular culture is informed by similar self-conscious, historically selective decisions; a facade incorporating classical and renaissance traditions, crafting an image closely associated with the landed aristocracy, yet almost entirely imported from other places and periods.

The interaction between cultural traditions in the construction of the country house went beyond simply following a view of western antiquity. The popularity of Eastern style had a marked impact upon the interiors of England’s 18th- and 19th-century homes.

We took a closer look at a Japanese lacquered chest, adorned with delicate flowers, pastoral scenes and pagodas, made for export and once in the home of a wealthy English patron. The appeal of oriental styles speaks again to a process of cultural cross-fertilisation, a product of new and expanding world markets, as well as changing aesthetic taste. It’s fascinating to consider how an object so seemingly in conflict with the quaint interiors we associate with country houses and National Trust properties, represents one of their key features – the complex interweaving of different styles and traditions.

The same discourse emerged from other objects in the Museum’s collection, including a narrative painting and a Pre-Raphaelite cabinet. There was little around us in the Museum that couldn’t be productively subjected to the same analytical framework.

Ultimately, it was revealing to see how our understanding of an English country house has been shaped by our own contemporary popular culture and that the image of what we associate with native tradition can be complicated by an understanding of the stylistic and economic currents, the traditions of appropriation and re-use which helped define English taste.

In the denouement of Pride and Prejudice, we hear Darcy making a recommendation to Elizabeth: ‘Think only of the past as its remembrance gives you pleasure.’ What this Wednesday afternoon at Krasis taught us was that objects and buildings can, if interrogated, teach us that pleasure, the past, and its remembrance are bound together in a more puzzling (perhaps even troubling) way than is apparent at first sight.

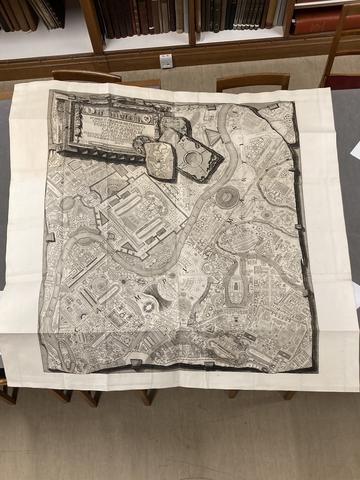

Week 3 was devised and led by AJTF Mathilde Daussy-Renaudin, who is a collaborative doctoral award-holder, working at Oxford’s History of Science Museum and University College London. Her research focuses on the labelling of astronomical objects and the use of categorical terms such as ‘science’, ‘religion’, ‘belief’, ‘Islamic’, or ‘European’, exploring their historiography and challenging the way we use them

This post was written by Krasis Scholars Giulia da Cruz, who is a 4th-year undergraduate in French and Arabic at Christ Church, and Daniel Morgan, a 2nd-year Historian from Lady Margaret Hall.

Re-using Collections

What stories is a museum telling us?

When looking around a museum, the most visible dynamic seems to be that between the artefacts and the public. Visitors from different age groups and backgrounds and with varying perspectives, interpret the artwork and objects according to their own unique frames of reference. However, another dynamic, equally important but perhaps not as evident, is that between the visitor and the curator. After all, although great debts are owed to the civilizations whose artefacts now fill the cases of the Ashmolean, it is the Museum staff who not only shape the public experience of the Museum but also, more importantly, tell the stories of the collections.

After the 2009 reconstruction of the Ashmolean, the Museum layout was no longer split neatly by department but was redesigned around the theme ‘crossing cultures – crossing time’. Jim Harris reminded us of the importance of the many decisions behind the layout of the Museum and the curation of the galleries. Indeed, what the public sees is not a random assortment of objects, but instead the result of recent and carefully-considered curatorial and managerial choices.

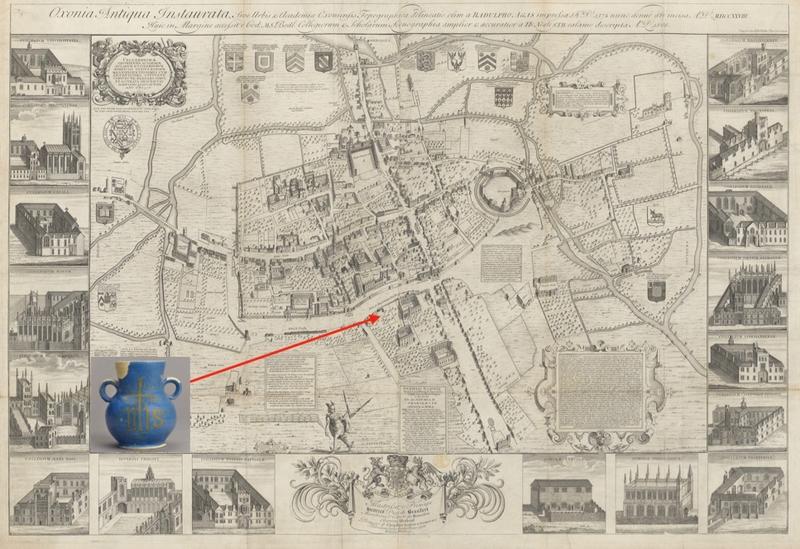

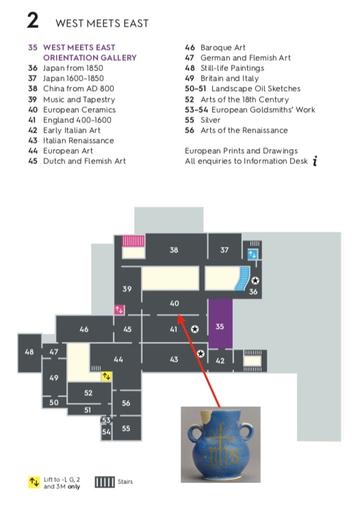

This week was led by AJTF Mathilde Daussy-Renaudin, who brought her research challenging museum labels and categories to the Krasis roundtable. Where better to start the session then, than in the ‘West Meets East’ gallery. The labels of ‘West’ and ‘East’ have an extensive literature of criticism, especially within History of Art. Unlike a usual visit to a museum, we focused on the labels beside each exhibit, rather than the objects themselves. This was an intriguing shift of attention. We realised that often we are so drawn to the range of the artefacts before us, that we find ourselves passively consuming the information beside it. In this session, however, we instead looked for the contexts behind the objects, both across their histories and their journey to the Ashmolean.

Our first response to the ‘West Meets East’ gallery was that it was based on clear, and perhaps rather reductive, periodisation. We noted how the displays, constrained by the nature of the collections, showcased luxury goods which had travelled from East to West from the 16th century onwards, thereby overlooking centuries of exchange and trade from before that point.

The gallery is therefore not so much a history of Eastern-Western interactions, than a showcase of the wide luxury trade in the (so-called) Age of Discovery, facilitated by advances in Western shipping and colonial expansion. Moreover, the generalist nature of the term, ‘Eastern’, was further highlighted as the majority of the objects in the room were manufactured in China or Japan.

The subheading for one of the displays, ‘Chinoiserie: a taste for the Orient’, prompted a discussion on the concept of ‘taste’. Taste is, of course, subjective but the western fascination with the ‘Orient’ has long been documented and ‘oriental’ motifs were once revered by wealthy elites across Europe. We also explored the connotations of feasting and consumption, especially with regards to the Western colonial project.

With many of the objects in this gallery manufactured for export to Europe, we felt that the ‘meeting’ between the ‘East’ and ‘West’ was rather one-directional, with most of the precious objects and resources permanently leaving Asia for Europe. Labels prioritised European provenance over Asian points of origin, and a set of porcelain vases, lacquered and with mother of pearl inlay, were described as being ‘from Althorp’ before any mention of their manufacture in Japan c. 1700.

The complexity of naming and categorising was evident in the label for a ‘Coromandel screen for a stately home’ purchased for a baronial seat in the English Midlands. It was of a type named for the coast from which it was exported in southeast India, but it was originally manufactured in China, and the label had also to include its final destination. As we can see, the European provenance of these objects has been highlighted, whereas the story of their production and manufacture are secondary, perhaps due to a lack of documentation.

In the second half of the session, Mathilde gave us the opportunity to curate our own hypothetical exhibition. Providing us with an individual object – a coffee cup, a snuff box, a gold coin – we brainstormed about the different ways these objects could be displayed. For example, displaying the cup in its intended setting, similar to the table setting in the Ceramics gallery; looking at its use, situating it next to objects of different origins but with the same function; or tracking its journey, both geographically and physically – from a clay lump to an enamelled coffee cup on a fashionable table.

After this session, it is likely that Krasis students will always walk around museums with a more critical eye regarding layout and labelling; and perhaps feel a heightened respect for the curators who have the challenge of deciding how to categorise and re-categorise objects that transcend geographical and chronological boundaries, belonging to many different cultures across their long lives.

Week 4 was devised and led by AJTF Dr Linus Ubl, who is Departmental Lecturer in German at Somerville College. His research interests lie largely in religious literature, for example legends and mystical texts, circulating in medieval Germany.

This blogpost was written by Kate van Riper, who is a visiting student from Brown University in Providence RI, reading English and Classics at Lady Margaret Hall, and Hector Worsley, who is in the second year of English and French at St Catherine’s College.

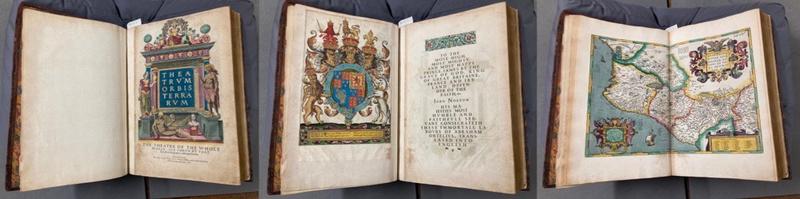

Re-using Books

Reconstructing Douce's Biography

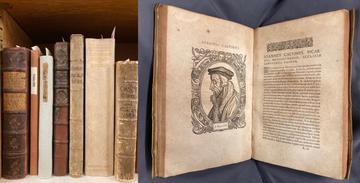

This week’s Krasis session focused on the collection of Francis Douce, an antiquary, collector and museum curator who left much of his collection of manuscripts, books, prints and coins to the Bodleian library on his death in 1834. Linus began by asking us a question: if we could take just one page from one single book to a desert island, which page would it be and why? The group’s answers ranged from the philosophical to the poetic to the practical (a map!). While this was a fun thought experiment, Linus also used the question to jump into a discussion about the process of removing an aspect of art or literature from its broader context.

He asked questions like: would you feel okay about cutting up your book to get your desert island page? How important is it for a book or collection (or the parts of a book or collection) to be stored together? These inquiries are relevant in the context of Douce’s collections, which feature many isolated pages and images that he either cut from their sources or found already dismembered.

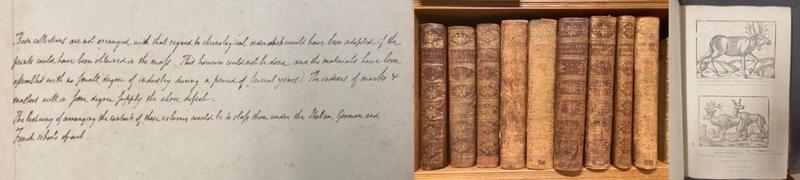

Kate: 'After getting to know Douce and his modes of collecting, we got to investigate some of his collection. Hector, Linus and I were assigned a box full of 15th-century German woodcuts, all cut out from their original sources. Together, we tried to figure out how the Ashmolean had organised them. Another group took on the task of examining two manuscript catalogue volumes describing the collection as organised by Douce himself and explained to us how Byzantine and idiosyncratic the system was. Other groups looked at unmounted prints still gathered in Douce’s own portfolios, and at prints he had cut out, stuck into albums and annotated.

Douce's Albums and his rationale for ordering their contents

'This exploration got us thinking about the many steps between the creation of an object or image and its collection and display in a museum. If Douce kept certain pages together, should the museum keep them together as well? After our discussion, I was leaning towards yes; though the idea of Douce tearing pages out of books is certainly jarring, Douce’s eccentricities added a whole new layer of interest to the collection.'

Hector: 'After a brief tea-time hiatus, we divided up to delve into the Museum's approach to transformed objects. Focusing on the Italian Renaissance gallery, Kate, Linus and I inspected a large, square painting of the Resurrection by Tintoretto. However, the painting had originally been octagonal and had been anachronistically altered to fit a square frame, with dark shadows added in the new corners and stitching visible on the surface of the canvas. Should the Museum keep the adapted sections?

Tintoretto's re-shaped 'Resurrection'

'Methods of overcoming this issue were suggested. The Museum could show the original form on the label, or perhaps deploy a projection to distinguish between the original and the amended shapes. Naturally, a compromise between the painting’s transformation and the museum’s display had to be struck: there is an inherent gulf between the Museum, an object's original setting, and the collection for which it was later altered. This led to an interrogation of a museum’s objective: should it principally be to educate (about the objects as it now exists), or to emulate (the objects's original state)?

'Other groups explored similar curatorial predicaments. The collection of antique statuary, together known as the ‘Arundel Marbles’ was at the forefront of discussions: bodies often did not match heads yet had been put together to create an aesthetic viewing experience. Whilst the decision made sense from a collector’s perspective, as the viewing experience was enhanced by seeing complete statues, this came at the cost of authenticity. However, it is also worth asking who has agency in these decisions? Collectors? Museums? The public is often omitted from the conversation, creating problems of the elite few gatekeeping art from the masses.'

Overall, the session made us interrogate the thinking behind the Ashmolean's public galleries and its collections storage and organisation. Museums act as beacons of education and must respect this power when it comes to their displays, overcoming potential obstacles to understanding, such as past acts of destruction, alteration, and censorship. Ultimately, we realised how it is impossible, and occasionally undesirable, for the past to be perfectly emulated and recreated (we cannot reconstruct Douce's dismembered books); yet education is only possible, and arguably enjoyable, when museums act as passageways into the (re-used, redeployed) wonders of the past.

Tracking down a print of John Calvin in the Douce collection

Week 5 was devised and led by AJTF Dr Tom Metcalf of Worcester College, who is a composer and lecturer in the Music faculty.

This post was written by Chloe Green, who is reading for a Music degree at Somerville, and Dominic Madera, who is in the second year of an English degree at Exeter.

Re-using Parts

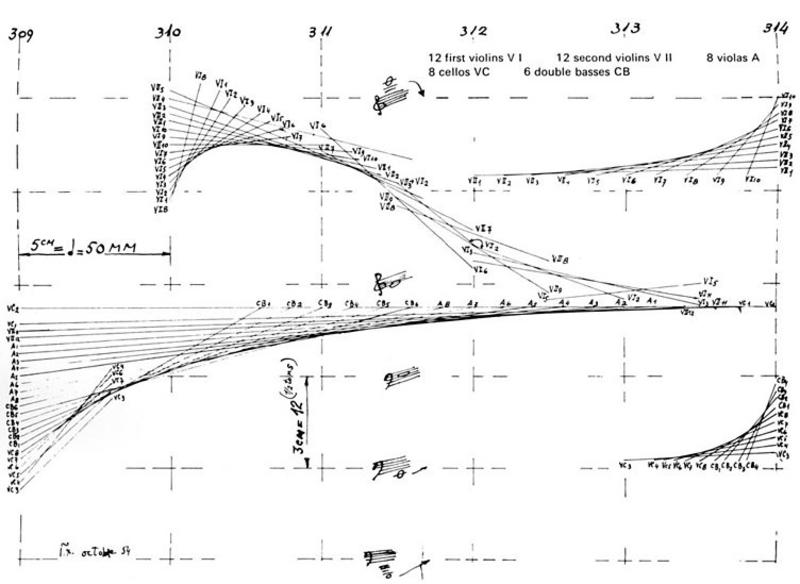

On a blustery February afternoon, Krasis convened in the basement café of the Ashmolean Museum, with music on our minds and in our ears. Prior to the session, Ashmolean Junior Teaching Fellow, Dr Tom Metcalf had shared with us an intriguing playlist, which juxtaposed works of Franz Schubert, George Crumb and Frédéric Chopin via Eugen Cicero and Tom himself. In response to this music, we asked ourselves, ‘what does it mean for an object to be an “original” or a “copy”?’ If an original object can be said to exist, does it change when transposed across geography and time? Do broken pieces of Greek classical architecture, for example, become a new object when rearranged by curators? Is meaning ultimately contingent on the audience’s interpretation of the object, or the context from which it is extracted?

Schubert's string quartet 'Death and the Maiden' annotated by Mahler

Gathered around café tables, we engaged in a metacritique of interpretation, interpreting the act of interpretation itself. Like you do.

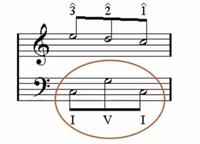

We began by problematising the topic of re-use in a musical context, starting with Schubert’s quotation of his own 1817 lied Der Tod und das Mädchen (Death and the Maiden) in his 1824 String Quartet No. 14 in D minor, D. 810.

From the concept of self-quotation, relevant in music and many other disciplines such as literary and aesthetic studies, we transitioned to the question of quotation more broadly. In Movement 6 of Crumb’s 1970 composition Black Angels (13 Images from the Dark Land), Schubert’s Death and the Maiden motif reappears, transformed.

Crumb’s instruction that his performers emulate ‘a consort of viols’, in ‘a fragile echo of an ancient music’, constitutes a contemporary relocation of a Romantic work into a distant past, evoking a complex tension between modernity and antiquity. The art of (re)interpretation reveals the intertextuality of relationships between 'original' and 'new' and destabilises these categorisations altogether.

The various soundworlds of Death and the Maiden delivered us into discussion of The Death of the Author, which Roland Barthes theorised in 1967. Is it possible ‘to give a text an Author’, in Barthes’ terms, where its creators are multiple? (In 1965, Eugen Cicero swings Chopin’s Prelude in E Minor.) Can nature function as Author also? (The trajectory of the River Danube structures Tom Metcalf’s 2020-21 composition Folyò.) Our critiques of the 'ego' and 'eco' alike foregrounded the role of live-ness in art, which we analysed through the lens of Walter Benjamin’s 1935 essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Benjamin’s notion of aura – the authority he ascribes to unique art works – and its decay readily suggested to us the possibility of analytical breakdown

Enter the assignment of the day: fictitious interpretation. Through this exercise, we delighted in creating alternative histories for objects on every floor of the museum, in dialogue with their labels. Our revisions provoked a range of responses, from laughter to serious conversation, as we radically re-contextualised ancient sculpture, 14th-century pottery, and 20th-century paintings.

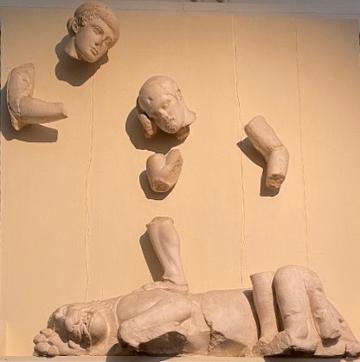

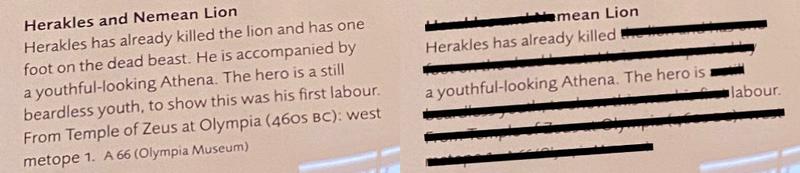

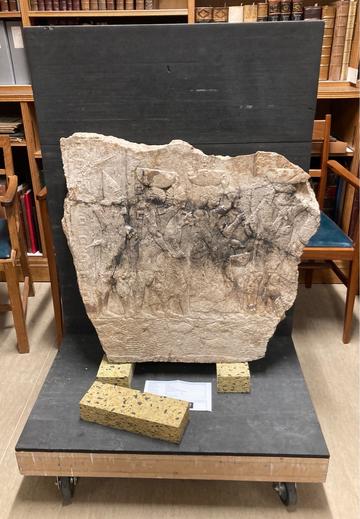

The Ashmolean's cast of the fragmentary metope of Herakles and the Nemean Lion

In the Cast Galley, for instance, we interrogated the negative spaces of Herakles and Nemean Lion.

The largely absent bodies of the supposedly living Herakles and Athena, and endurance of the ostensibly dead lion, led us to view the work from a post humanist angle. Nature lives on in death; while all that remains of humankind are remains themselves, these disembodied heads and joints, our minds and our movements.

In this light, the dead lion transforms, paradoxically, into the most human figure within the display. What was once Herakles and Nemean Lion becomes, to us, a noli me tangere, or touch me not: an exploration of the way we, as contemporary viewers, are drawn to the lion’s suffering over the disembodied limbs of the demigod and goddess. Negative space generates intertextual reuse and adaptation, and, from there, a new object.

The missing elements of the cast inspired us to ekphrasis: influenced by 'erasure' or 'blackout' poetic techniques, we reworked the original label to support our new materialist interpretation. The activity led us to the conclusion that making meaning always leaves phantom traces of originals and copies. Processes of adaptation and reuse invite a multiplicity of perspectives on objects, which incorporate various interpretations – of curators, scholars, museumgoers, and more – into their histories.

A vital aspect of Krasis is its interdisciplinarity. With Tom at the helm, we brought musicology to bear on the Ashmolean collections. In Lydia Goehr’s seminal 1992 musicological text, The Imaginary Museum of Musical Works, she explicates the ‘work concept’ in music. Goehr’s writings might encourage us to consider 'artwork' more generally as 'art' plus 'work': as our reworked label reads, ‘the hero is labour.’ Although, through Krasis, we occupy a very real museum (as opposed to Goehr’s imaginary one) our imaginations certainly, and fortunately, flourish within.

Part of this imagination comes from the intellectually demanding task of engaging across disciplines. Through our experiences of two divergent academic fields (Music and English Literature, respectively), we exercised our academic and aesthetic imaginations within the symposium. As we exited the Ashmolean into the Oxford early evening, Tom concluded, ‘I hope you learned something – or unlearned a lot of things.’ Both were true.

Week 6 was devised and led by AJTF Chenying Liu of Wolfson College, who is a DPhil researcher in Engineering Science working on origami, folding technology and soft robotics

This post was written by Deanna Cunningham, who is reading for a Masters degree in Archaeology at Hertford College, and Seren Atkinson, who is a 2nd-year undergraduate in English at Christ Church.

Re-using Shapes

On an unsuspecting, drizzly, Wednesday afternoon, eight students and four ECRs were about to have their minds changed forever by the technological genius of this week’s teaching fellow, Chenying Liu. Krasis is designed with the principal aim of bringing together teachers and students of different academic backgrounds to challenge and expand our ways of thinking, which could not be a sounder way of thinking about our experience on that rainy day!

Chenying’s session focused on what origami is and how it might be used: thereby bringing together the disparate strands of arts and sciences and showing us that they were not so separate after all.

Before we arrived at the New Douce Room, Chenying had requested that we each make a piece of origami and bring it with us. As we convened at the table, both of us felt slightly ashamed at our lack of origami skills, with two (slightly battered looking) butterflies to show for our efforts. Much to our relief, Chenying’s subsequent request was that we flatten our creations back into paper. We then began to look more carefully at the crinkled indentations left in the wake of our origami shape. The fact that our tiny creations were made of paper was, of course, important, but the tiny mountain and valley folds - a technical term we soon found out - were what transformed the possibilities of a single piece of paper.

Etymologically, Chenying explained, 'ori' means to fold in Japanese and 'gami' comes from the word 'kami', meaning paper.

However, moving from paper to clothes formed our next challenge. As we rolled up the various tea towels, shirts and socks we had brought with us, we considered what our acts of folding involved and why we performed them. Most of all, our folding made our various articles of clothing more compact and neater, making storage more efficient.

Chenying revealed that the economies of space generated by folding materials characterised much of her doctoral research. It was at this point that our minds were about to be blown.

For engineers seeking to put technology or people into orbit, Chenying explained, utilising shapes that could be moulded and changed, as well as maximising space, was essential. This is especially crucial for power sources that rely on solar energy once in orbit. Tapping into and maximising the potential of solar panels is, therefore, one of the main challenges facing engineers like Chenying.

We soon discovered that our experiments in origami and clothes folding were merely a warm-up for one of the biggest dexterity challenges of this, or indeed any Krasis. Arriving fully equipped, Chenying handed out sheets of paper marked out with the pattern for making our own mini solar panels.

We set to folding the mountain and valley lines correctly according to the instructions on the NASA worksheet (which you can find here). After 20 minutes of intense focus and a few difficulties in getting the final flourish that twisted the solar panel to life, we each had made our own mini panel (see the picture!). We felt oddly emotionally attached to this little bit of paper, and one of us, not to name names, still has theirs proudly on their desk.

Having created these paper solar panels, we thought about the limitations of what we’d made. Even with our collectively limited STEM knowledge, there was a consensus that paper was probably not a good material for storing solar power and that other materials would have to be used instead.

Chenying, ever resourceful, brought out a box of what can only be described as ‘drywall-like’ 3D triangular chips. We were then tasked with joining and creating possible solar panel shapes with thicker materials. We set about sellotaping triangles together in small groups to develop flexible, robust structures. Descriptions of these structures escape us, and our drawings are not much better; as per this quick sketch! However, if you want to see our tiny, folding structure you can see it here on Krasis twitter.

Having completed and been utterly mesmerised by our moving constructions, Chenying showed us the larger and more complex structures she’d built. These caterpillar-like structures were fluid and moveable only in specific directions, whilst others were rigid and solid. There are infinite possibilities inherent in sheets of material that can be manipulated or joined together. The triangles, either equilateral or isosceles, moved in regular and predictable ways.